On Alberto Giacometti, Edward Hopper, and Literary Deliverance

A Conversation with Peter Orner

Today marks the release of Peter Orner’s second short-story collection, Last Car over the Sagamore Bridge. (This collection includes a story from WLT’s January 2013 issue, “Renters.”) In the conversation that follows, WLT’s managing editor asks Orner about his work, the writers we should be reading, bibliotherapy, and the power of literature to both deliver and completely undo us.

Michelle Johnson: On August 6 your new story collection, Last Car over the Sagamore Bridge, was released. After writing your second novel, Love and Shame and Love, you’ve returned to short fiction. How has your work evolved since your highly regarded 2001 collection, Esther Stories?

Peter Orner: The truth is, I’ve never left; I’m always, always writing stories. I love novels, too, but in a different way. I always say that if every novel in the world suddenly disappeared tomorrow, I’d be okay so long as Chekhov didn’t go anywhere. I think maybe the difference between Esther Stories and this new collection is that back then I didn’t know I didn’t know what I was doing. Now I know I don’t know what I’m doing. And this: I’ve always felt there was a great deal of power in not talking too much on the page. In Last Car, I’ve taken this further, maybe. I find a great deal of the intensity of a story lies in what is unsaid.

MJ: What’s next? Will you continue writing stories, or is there another novel in the works?

PO: As long as I’ve got a breath left, I’ll keep doing this, in my own slow way. A novel is in the works—it might take a decade to finish. Don’t tell my publisher this. And more stories, always.

MJ: Loneliness is a recurring theme in your writing, though you seem to have an ambivalent view of it. Most overtly, you are “The Lonely Voice” for the Rumpus, and you explore your own desires both for it and to escape from it in your column. And your brother, Eric, who created the illustrations for your novel, said that you wanted to evoke “a landscape of loneliness.” What’s with you and loneliness, and how do reading and writing figure into your relationship with it?

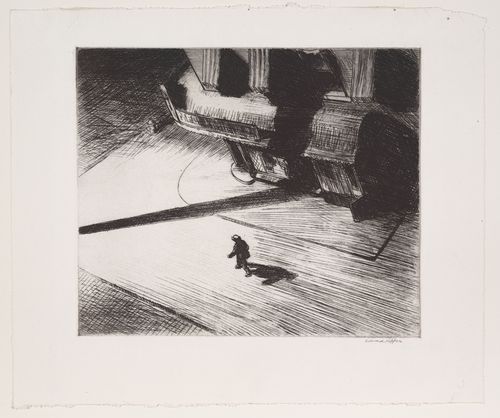

PO: Wow, Michelle, where to start? I’ll spare you the treatise. I find loneliness to be so basic to being human that it is almost funny we need an actual word for it. As if we could be anything but. Even surrounded by family, by friends, by strangers. And it can be painful, living is, so is dying (what’s more alone than a grave, even if it’s near those you loved?)—and yet I also find that it can be, for me, a positive thing. I think much of what makes us individuals is our own peculiar form of loneliness. I try, when creating characters, to think about this. What’s Jeanine’s loneliness like? What about Fred’s? Like a lot of people, I’ve always been drawn to Edward Hopper’s work. Why is it so inspiring? Maybe because we see ourselves. Here’s a drawing I like from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s called Night Shadows. I like it better than Nighthawks, which is (a) too famous, and (b) has too many people. But the people, of course, don’t make even Nighthawks less lonely.

MJ: Do you think social media is buffering a feeling of loneliness for some?

PO: No clue. But maybe there’s no need to buffer it?

MJ: You’ve written about your reluctance to enter the social media frenzy, and you seem more comfortable promoting other writers, particularly those who haven’t yet received the attention they deserve. Can you share a few writers with us, those we might otherwise miss?

PO: Lately I’ve been reading and loving an Elizabeth Bowen novel called The House in Paris, but I’m not sure Bowen needs any props. She’s very much still in print. Three of my favorite American writers—and to my mind absolutely essential American writers of the last fifty, sixty years—are, first, Gina Berriault, who wrote the seminal stories that are collected together in Women in Their Beds. The delicacy and beauty of Berriault’s sentences is almost unsurpassable, but above all it is her characters, her people, that get under your skin. Recently, I read a breathtakingly beautiful short novel by her as well, The Lights of Earth. So she could do it in novels, too.

The second is Wright Morris. I’m always trying to get people to read him, and rarely do I ever succeed. But Morris, who won all kinds of awards in his day, including the National Book Award twice, is too often overlooked today. He wrote remarkable and one-of-a-kind novels: The Field of Vision, Ceremony in Lone Tree, Plains Song, A Life. The list goes on and on. Stylistically, he can be difficult; he was a disciple of Faulkner in some superficial ways, and yet so completely different not only from Faulkner but from anyone else writing in his day—anyway, I could go on and on about Morris. I always do; nobody ever listens. I think about Tom Scanlon sitting by the window in the opening pages of Ceremony in Lonely Tree and I want to weep—and laugh. Morris is that good: a man looks out a window and I think about it for years.

Third, James Alan McPherson, a mentor and teacher to me, as well as so many others. What McPherson taught in class, and in his stories and essays, is that at the end of the day, this is all about human connection. No matter how bad a story was, he always looked for what made it human. And if it was a good story without any humanity, he made that call, too. It was less about the writing than whether you were addressing something more fundamental: are your people alive to each other? His books, Hue and Cry, Elbow Room, Crabcakes, A Region Not Home . . .

MJ: I read your column about throwing a novel out your car window (I worried about you a bit—reading at a red light in your car). You go on to say, “Maybe this time I will find the one book that will save me from myself.” Do you believe that reading can offer this kind of deliverance? Have you experienced it?

PO: By the God I have trouble believing in, yes. I do believe literature delivers us. Where is the question, and the where is always different. But, just for instance, start with a book from the above, McPherson’s Crabcakes, a book that reminded me that unless we focus on our shared humanity, we’re doomed. Here are a couple of lines from that book. It’s McPherson writing to a friend in Japan who taught him, among other things, the value of being silent:

I do the best I can by, periodically, dropping into silence . . . in order to renew myself. . . . I have this old resource back now, and I intend to try very hard to never lose it again.

MJ: I’m intrigued by the Center for Fiction’s bibliotherapy offering: after a personal consultation, the center will recommend a year of reading materials that relate to a major life event. What are your views on literature’s therapeutic properties?

PO: This sounds great. Any program that zeros in on books that people might not know about, I’m all for. And the Center for Fiction is an invaluable and incredibly unique resource. A whole building in New York devoted to fiction: what more could anybody want? As for the therapeutic properties of fiction, I’m not certain about this one. Sometimes fiction has them, sometimes not. I do remember once reading an Anne Tyler novel—was it Searching for Caleb? That book saved me from me from myself; I know this for sure. But in general, therapy is supposed to help build us back up. Fiction, in many cases, is designed to knock us on our ass with the truth. So I think it varies. To my mind, fiction’s just got to be emotionally honest, whatever the cost.

MJ: In Steve Stern’s story “The Man Who Would Be Kafka,” a boy reads Metamorphosis and becomes a Kafka disciple: “The truth was he didn’t travel at all, obedient to Kafka’s dictum.” Well into middle age, he finds himself teaching a Kafka course in Prague and contemplating his choices. Do you believe reading has the power to change us, even reroute us?

PO: Talk about fiction knocking you on your ass. Steve Stern’s work does this, but I’m usually too busy laughing to have noticed, shit, he just pulled the rug out and now I have to deal with every mistake I’ve ever made in my life. I’d say I’m lukewarm to therapy, a resounding yes to rerouting. If I hadn’t read John Irving’s Cider House Rules in 1988, I’m not sure I’d do what I do. Nice to think of these foundational books, books I sometimes forget about, books I used to get so lost in. Irving, Tyler. Thanks, Homer Wells. And I also think, damn you, Homer, I could have been rich or something if I hadn’t been rerouted by you and your fellow orphans. . . .

MJ: Let’s talk lawyer-to-lawyer for a minute. The notion that reading can be dangerous has fueled a fair amount of moral panic and litigation—think back to the 1950s war on comics—and branched into battles over federal and state government controls of cyberspace and violent video games. You recently served as an expert witness in a case about werewolf erotica, in which you attested to a novel’s literary value after a California prison blocked a prisoner’s receipt of it. Though that case was primarily about obscenity, California’s penal code allows prisons to refuse books that incite violence. If books can break our hearts, can they also stir us to violence? Can one be true but not the other?

PO: I agree, books can be dangerous. And the genius of the First Amendment is that Jefferson and Madison and all those guys knew this, and they also knew that the freedom that comes with that risk is so potent—they could create an entirely new way of living for people. Has it panned out? No, but the inherent dangers in the freedom of speech, of ideas, always make it possible for things to actually improve. I’d also say that books are dangerous, yes, but hit someone on the head with one, they won’t die. I mean this literarily. Hence, I’d say they made a mistake with the Second Amendment. This we’ve taken too far. Know what I mean?

MJ: You praise story writer Peter Taylor’s beauty and subtlety in your first Lonely Voice column. When I read that, I realized “subtlety” was a word I’d been searching for as a reader of your stories. Whether I’m reading your short fiction or one of your novels, I feel like you’re trying to quietly break my heart—and with as few words as possible. Why do you so highly value compression? Or to use your elsewhere praise of Giacometti’s compression in his waifish figures: why not a Botero?

PO: Botero? He does those chubby guys, right? I like those guys, but I think about those legions of thin people walking, walking. . . . I don’t know; they just do it for me, and you can feel Giacometti consciously not adding flesh. There’s something so moving, for me, about that restraint. We’re all, whoever we are, just tall thin people walking, walking. . . .

MJ: One of my favorite analogies for your work is by Tania Hershman, who called your stories “Tardis-like: just as Doctor Who’s police-box spacecraft appears small from the outside and is cavernous within, so these stories, often only several pages, contain depths and layers far larger than the sum of their words.” Considering your mastery of compaction, I have to ask you: where does poetry fit into your life? (And our readers will also want to know if you’re a Doctor Who fan.)

PO: That’s a kind thing to say. I have a friend who is a Doctor Who nut. Shout out to a very good writer, Junse Kim. I’ve never seen the show. Is it on the BBC or something? I only watch Mary Tyler Moore reruns on Nickelodeon. Does this date me? I do read a lot of poetry; every day I probably do. Today I read a poem by Franz Wright I didn’t understand, but it didn’t matter, I get what he was trying to say. Something like, hold on, just try and hold fucking on. . . .

MJ: Your concise writing style and skillful sentence design render you perfectly suited for writing the legal briefs judges are eager to read. How did your legal training impact your writing style, and are you ever tempted to return to legal practice?

PO: I was never tempted, but I’ve done some immigration work, which I enjoyed, but I also found that I wasn’t meant to be a lawyer. I’m not focused or even smart enough, and my clients deserved better.

MJ: Your nonfiction book projects seem to spring from a lawyer’s impulse to tell a client’s story but to do so through the client’s own testimony. Underground America records the narratives of undocumented persons in the US; Hope Deferred the narratives of Zimbabweans. In both projects, you’re using narrative to bear witness to the lives of people who might otherwise be subsumed by stereotypes, reductive metaphors, and TV sound-bites. What led you to this work?

PO: The fact that I knew I was never going to be a good lawyer, but my interest in law led me to these nonfiction projects where I could interview people about human rights abuses—but not in a legal way, a story way. The law does tend, I think, to box things up in a way that is exactly the opposite of what stories do. The law is a sledgehammer, a necessary sledgehammer, but stories, for me, do so much more. I think in both books, Underground and Hope Deferred, we were able to shed light on the lives of people that are otherwise stereotyped. Oh, you’re an illegal alien, I get who you are. Oh, you’re the resident of a screwed-up African country with a ruthless dictator, I get who you are. In making these books, I end up spending hours and hours with people. It all comes down to getting to know people, and to know people you have to put in the time. I’m proud of the work we did in those books, and feel honored that so many people have given me the gift of their time.

MJ: You’re now working on a project in Haiti. What are you doing there, and what will you be writing about it?

PO: I’m working on a new oral history set in Port-au-Prince for McSweeney’s / Voice of Witness. (The other books you mentioned are also from this series.) My co-editor is Evan Lyon, a doctor and writer, and, along with Katie Kane of the University of Montana and Doug Ford of the University of Virginia, we’ve been interviewing residents of this remarkable and very troubled city. I’ve been to Port-au-Prince twice now, and I’ve seen some amazing things, many of them very positive, some horrific. Mostly, though, I’ve met some wonderful people willing to speak about their experiences before and after the earthquake. The book will be about the trials and triumphs of surviving in a city that functions differently than most cities. And functions is the key word because Port-au-Prince, I’ve found, does function—in its unique way—through social networks and family. Again, it comes down to individuals. I hope the book surprises readers into seeing Haiti not as a hopeless basket case but as a country full of people with a great deal more than we realize.