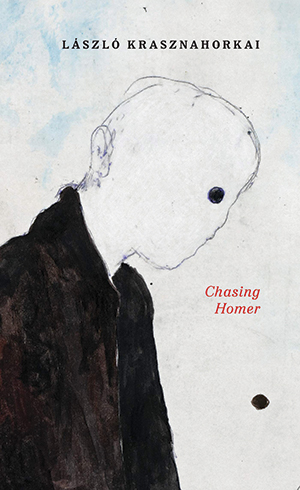

Chasing Homer by László Krasznahorkai

New York. New Directions. 2021. 91 pages.

New York. New Directions. 2021. 91 pages.

HUNGARIAN AUTHOR László Krasznahorkai is gifted with seductive powers that force us to go wherever he goes; we simply cannot negate him. In Chasing Homer, his anxious first-person narrator careens at breakneck speed through the vastness of Europe’s haunted spaces. We wonder why he is running so fast and from what. We know nothing about him; not his name, or whether he is a parent or father or husband or someone’s lover, or even if he is a good or decent man. He offers no confessions.

Yet in a few short paragraphs we are entranced by the lusciousness and foreignness of his impossibly long sentences, which are unencumbered by any internal pressure to come to an end. His suffering becomes ours. We understand he’s under attack—by men who have deemed him unworthy to live—but he offers no clues as to why they want him dead. What was his transgression? Was there one? We aren’t really certain other than knowing that they simply want him to die. It’s not that we are naïve. We know that this last century has seen millions of men and women die for no reason at all; so many at the death camps in Europe, but Krasznahorkai, or rather his unnamed alter ego, never speaks of the Holocaust or any other atrocity directly. He seems disgusted by man’s barbarity to man in all its reincarnations. He describes for us proudly how he has survived this long in intricate passages telling us about the ingenious ways he slips in and out of a crowd without being noticed, or how he is able to remain hidden in the hull of a boat for days at a time without being detected.

Krasznahorkai’s protagonist focuses his intention on surviving, which requires him to keep moving, often in counterintuitive directions, to throw off those chasing him. He finds remaining constantly vigilant exhausting. We don’t sense he yearns for any human contact, and he never reminisces about someone he misses from his past. It seems the fight to stay alive has extinguished all other preoccupations. One might think this would distance us from him, but the unfathomable thing is his ability to create in us strong feelings for him despite his obliviousness. We feel his agony and want to help, but he continues to ignore us.

His narrative is enhanced by melancholy portraits by German painter Max Neumann that are for the most part indecipherable. The first one we see is a simple line drawing of a man with his eyes blacked out, and another painting shows three men in shadow seemingly scanning an interminable landscape. Another shows a man with a bat seemingly preparing to defend himself against a gang of pursuers whose faces are shielded from view. The book is also accompanied by the madly percussive music of Szilveszter Miklós, made available to the reader by QR codes, which adds to the apocalyptic tension that ripples through his prose.

I recall only one time when his voice possessed yearning for a past now long gone. “I never received any training in the skills my life now depends on,” he writes; “my education was about different things entirely. I’d been taught Old High German and Ancient Persian and Latin and Hebrew, and they’d instructed me in Mandarin and Japanese of the Heian era.” We wonder why he is telling us this. Do we hear the faintest drops of some sort of latent elitism for an earlier time? We aren’t certain. All that is clear is he remembers this time with a happiness that is no longer present and we wonder if this joy had something to do with providing for him some moral guidance in a world that already confused him.

It occurs to the reader that his prose is strangely silent with regard to moral reckonings of any kind. The author shies away from philosophical assertions, choosing instead to angrily riff on the idiocy of mice and his outrage with the scientists who torture these brainless creatures in their absurd experiments. He is equally disturbed by the entire field of mathematics and its inherent fraudulence postulating that any field that proposes that one plus one equals two should be wiped off the map, because we all know it never really does.

The author is private in interviews, and whatever he does say seems thwarted by an undercurrent of concealment. We wonder about the heavy sadness that runs unrestrainedly through his works. His Hungarian father was a young Jewish lawyer living in Hungary during the time that place was one of many places extinguishing Jews. His Gentile mother, by marrying him, became an accomplice to this insanity, as, in a sense, did he, the product of their unholy union. Krasznahorkai never speaks directly about the Shoah, or his father’s heritage, which is partially his own, and I wonder if all of the underlying chaos and pain expressed in this book, and many of his others, is really his own muted horror about the suffering and fear his father most certainly faced. A fear that is now his own. With Kafkaesque brilliance, he re-creates his parents’ world as well as the bleakness of the post-Holocaust world he was born into in 1954. But he is careful never to address any of this head-on, because he understands that to label something is in some way to instantly diminish it, and he doesn’t wish to do so. Like an agitated W. G. Sebald, he prefers to show us instead.

Elaine Margolin

Hewlett, New York