In the Den of the Voice

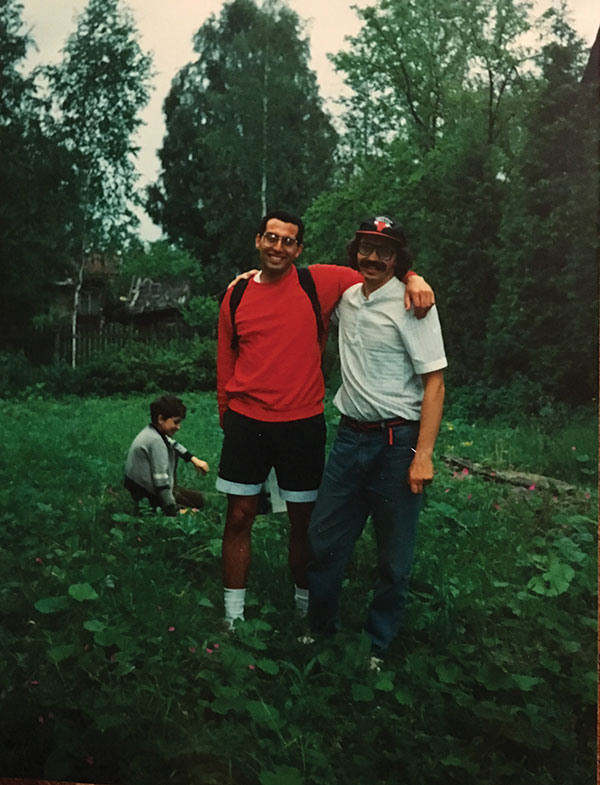

In the Den of the Voice” is part of The More You Love the Motherland, a memoir of the author’s year talking with poets in Russia during its most tumultuous years transitioning to capitalism (1992–93), and features Dimitri Psurtsev, a noted poet and translator.

“Look inside,” Dima said, gesturing to me to peer between the slats of a tall gray fence. We were on the outskirts of Moscow, halfway to his mother’s old apartment—what we would come to call “The Den of the Voice,” where we would wrestle with Russian poetry and language and each other.

I peered in. Across an overgrown yard, stone plinths and busts of heroic men—some in helmets, some decorated with epaulets—were strewn haphazardly in the dirt, as if tossed away. The factory looked like it had been abandoned, but to my eyes, most buildings in Russia looked either condemned or unfinished. It was the fall of 1992, when everything was either dying or not yet born—not yet post-Soviet, and not really free.

“Who are they?” I asked. Just about everything in this country induced a question in me, and that question would produce a further question—a matryoshka situation of questions nesting inside questions.

“They used to make statues of Lenin and other Soviet leaders here,” he said, in his clipped, semiposh English. “In the time of the USSR, each city had its own Lenin. In one town, a huge Lenin statue stands, pointing into the distance. If you follow the direction of his finger, you find yourself at another smaller Lenin. He’s also pointing. If you follow his smaller finger and look closely in the nearby bushes, a tiny Lenin stands.”

I laughed.

“There in the bushes, where a drunkard sits and drinks and sings, a little Lenin sits with him.”

I laughed again.

“I’m not joking,” he said. His eyes gleamed with wicked delight, a smile widening on his face, as I laughed in wonder at this place.

When I’d called him and heard his arrestingly British accent, precise as a razor, I could hear his wit and gentleness and wisdom and knew he would be a door to the mysteries of Russia. He’d been close friends with Tatiana Tulchinsky, whom I’d met in Chicago to work on my Russian. One day, she’d handed me a sheaf of seemingly ancient typescript called Ex Roma Tertia (From the Third Rome), a play on Ovid’s Epistulae ex Ponto (Letters from the Black Sea). I was instantly pulled in. In his poem “Inhabitant of the Third Rome,” Dima creates a self-portrait in a comic, transcendent mirror:

In wintertime, I love to wrap myself

till fat and warm,

To dress in two pairs of pants, tall

boots and mittens,

To don a coat of fur – even if its fur’s

completely fake –

Then strap the earflaps of a wolf-fur

hat around my chin.

This wind’s so brutal, it’s good I’ve

got Polovtsian slits for eyes.

Though this cruel frost can’t pierce

my Tatar cheekbones,

My mustache turns white with ice, my

blood thickens like cold vodka.

So here I stand, happy inhabitant of

the last, the Third Rome,

Reforged barbarian, heir, and –

perhaps – future ancestor.

I’ve drawn my breath on its quick

and eternal air.

THE VOICE WAS AT ONCE comic and prophetic; I imagined that the poet who made it loved his mongrel background and his country—all its layers of history, which led him to this cold and eternal moment.

I would come to learn, while poring over poems together, that he was as entranced by Russia as I was. For as long as he could remember, he’d been writing poems that found the transcendent in the mundane world around him—waiting for the train in the dead of winter, sitting on long bus rides with babushkas in the country, writing letters to émigré friends, toiling in the dacha garden, drinking vodka and looking at the stars—everything vibrating with folklore. The prospect of bringing me along his poetic and spiritual journey through the mysteries of Russia only lightened his burden.

In his poem, he refers to Moscow as the Third Rome. I was fascinated by the notion of Moscow as the center of civilization—that, once Constantinople (the Second Rome) was taken by the Ottoman Empire, a new center of Christendom must arise, and Russia was grandiose enough to believe that it must be in Moscow. By the time Philotheus of Pskov declared in a letter in 1510 that “Two Romes have fallen. The third stands. And there will be no fourth,” Russia had secured itself not only as the center of the Christian world but also as the last bulwark between civilization and the apocalypse.

What would it mean to love one’s country, I wondered, wanting to love their country, the country of Pushkin and Chekhov and Tolstoy and Akhmatova?

It’s a sentiment felt in Russia to this day. It goes some way to explain the ideology that undergirds the support for Ivan the Terrible, Joseph Stalin, and even Vladimir Putin. Dima embraced the idea of Russia’s special place in Christendom, and though he was no fan of the Soviet Union, he was deeply patriotic and loved his country with an alacrity that I envied. Still reeling from the blood circus of the Persian Gulf War, I thought of my country as a land of lies, where the brutality of the fist was worshipped over the tenderness of the hands, where money ruled and gentleness was considered weakness. What would it mean to love one’s country, I wondered, wanting to love their country, the country of Pushkin and Chekhov and Tolstoy and Akhmatova?

“I will see you at Mytishchi train station,” he said over the phone, organizing our first meeting.

“I will look for you,” I said.

“You won’t need to,” he said. “We don’t see your people around here.”

At the station, he made himself known immediately, as I trailed the commuters bustling off the elektrichka. In his early thirties, his black hair thinning at the top, thick glasses matched by his thick mustache. He reached out his hand, leaning his whole slender body forward, as if he were going to shake hands with his spine.

With his mustache, wire frames, and propensity for jokes, if he’d grown up in the States, Dima might have been a Marx Brother, not a Marx Worker, busting his ass to translate everyone from D. H. Lawrence to A. S. Byatt.

“I’m working on Frank Baum—the Oz series,” he said on the walk to the apartment, proceeding to explain one translation problem after another. How to translate a name like the Tin Man, for example, in a way that delivers the punch of the original yet has the uniqueness of Russian. He threw himself into the alchemy of analogues with the furious zeal of the converted, trying to bridge our distant languages and cultures, English and Russian, his brain inhabiting both worlds even though he’d never been out of the Soviet world.

Every week, we’d meet at an old efficiency in Mytishchi, the Den of the Voice, where he once lived with his mother before she’d moved to the dacha. That first day, when he turned the key and flipped the lights, I smelled a slight must, as if the place had sat still for years, decaying slowly, waiting for us to enter. Like an old person sitting quietly, biding her time for a guest coming from far away. It was a single room, with bars on its first-floor windows, two couches lining the walls, a phonograph in the corner with a small stack of records, a bookshelf with a handful of books, and around the corner, a sliver of a kitchen and a bathroom. That was it. But what we opened in that little space was like the wardrobe to Narnia.

I was always asking questions, and Dima was happy to have answers. This was the way we worked, foraging through not only poetry but also language and culture and religion and art history and music—our crash course in Everything Russian. Sometimes, though, his ideas would fail his hilarious English.

“I feel huge,” he once said, after trying to explain a complex idea in his nonnative tongue. “It’s like wielding an axe at the dinner table, when a knife would do.”

Dogged by loneliness, amped on tea, haunted by the nastiness of city life in a declining empire, I was often awake, living like an American ghost on American time in Moscow.

One week, he’d been working so hard to meet a deadline to produce a translation, staying up for days, his heart began to ache with angina. The truth is that I may have also contributed to that squeezing in his chest. He’d given me extensive translations to do at home, and when my work didn’t meet his standard, he grew vexed, snapping at me—exhausted from teaching translation all day and then doing the night shift with me. I’d made stupid mistakes, confusing “meadow” (lūg) for “onion” (lūk), and complained that I wasn’t sleeping well, which tore at my focus and attention to detail. Dogged by loneliness, amped on tea, haunted by the nastiness of city life in a declining empire, I was often awake, living like an American ghost on American time in Moscow. The bridge that he could make in his brain would often fail to meet in mine, as I’d stand, pissed at the limits of my languages, gazing over the abyss to the distant Russian shore.

In a notebook from that time, I happened to find a passage from the Book of Revelation:

And I went unto the angel, and said unto him, Give me the little book. And he said unto me, Take it and eat it up, and it shall make thy belly bitter, but it shall be in thy mouth sweet as honey.

And I took the little book out of the angel’s hand, and ate it up; and it was in my mouth sweet as honey; and as soon as I had eaten it, my belly was bitter.

And he said unto me, Thou must prophesy again before many peoples, and nations, and tongues, and kings.

I READ THIS NOW as if it somehow were a key to what I was witnessing in Russia, or a key to what was happening to me—two threads that I can’t unbraid—and what I hoped would come of my eating this huge book. By the time I acclimatized to Russia, when the early romance of it burned away in the sadness of it, I could not love Russia from afar. It was bitter, but the bitterness of eating the book of Russia did not turn sweet in my mouth. It grabbed my tongue and twisted it into gibberish and silence.

I’d wanted to believe what Russians had suffered was something that had strengthened their spirits, that could strengthen my spirit. Russia is very good at suffering, at seeing suffering as a door to some insight that would not arrive otherwise. In theory, it sounds beautiful.

“Did you ever notice that when you shave your hair, it grows back even thicker?” Dima said.

We were in the small kitchen of the Den of the Voice, waiting for the apple cake to brown in the oven, taking a break from translation and needing to warm up. The Den never got warm enough, unless the oven was on, and then it would gradually cool, sending us under blankets for the cold night. We’d named the place after the title of a book by Yunna Morits, whose dazzlingly sonic word combination in Russian suggests both a primitive animal cave and the heights of human expression.

“It does?” I said. I hadn’t been shaving long enough to observe that.

“Perhaps it’s the same way with us,” Dima continued. “The more we’re pared away, the stronger our souls grow.”

It was a compelling idea. So, too, amid the trials of living here, the souls of Russians could grow. Dima held to a view that so much of our lives is not within our control, and that our embrace of humility was paradoxically a way of growing closer to God. You could read it in the torments of the novels of Dostoevsky—how Rodion Raskolnikov had to descend from his murderous arrogance into a final acceptance of his powerlessness and his fate. So, too, I hoped, that in Russia my soul could grow.

As Dima writes in Image (94):

Today, having swigged a half-liter

Of lemon vodka with a friend,

I, a vegetable garden crawler,

Take in the light of distant stars.

They are galaxies, I know,

But they seem like turnips to me:

He who sowed them, one day,

Will pull them out by the hair.

Today I saw how a guess

Staggered in the desert air –

Rain sprinkled on the dill

And vouchsafed to me:

I am here to live humbly,

Letting my root into infinity,

I am here to become powerless,

And, without power, become strong.

I ADMIRED AND LOVED this sense of homeliness and humility in the face of so much that was ugly and inhuman about this country. That what was our humility and powerlessness could allow us to grow into infinity. But what if our powerlessness just ground us down and robbed us, not only of our freedom, but our voices as well?

IN THE BRIEF HEAT of a Russian fall, beneath a copse by trees drenched in reddish gold, I rested on a blanket spread along the grass, with Dima and his wife, Natasha, unwrapping sandwiches and cutting apples we had picked from their dacha in Pravda. We’d been scrounging this forest in Peredelkino for acorns and berries, filled with that eternal feeling of autumn just before the leaves disappear, the trees tuck up their sleeves, and everything sleeps. The air was clear like the mind of someone who knows that they will die soon.

In the distance, a church cupola gleamed golden in the amber trees, and even the giant apartment blocks that dominated the far sky, like dingy quadruplets, seemed just symbols of something, not realities of the leaden bruteness of Soviet power.

“How did the Revolution fail?” I asked Dima, taking a bite of a blackened banana I’d brought from a kiosk and forgot in my backpack. We were picking up on a recent conversation we’d been having about the Russian impulse toward community and its Soviet iteration as collectivism.

“You seem to have in mind Trotsky’s concept of ‘perpetual revolution.’ As if the revolution had continued to the present day,” Dima said, stabbing an apple slice and taking a big bite. “The Revolution failed in 1918, at least morally, when Lenin began the purges of the kulaks and the forced collectivization of farms.” According to most sources, the state forced millions of small farmers—kulak means fist, because they were allegedly “tight-fisted”—to give up their land. Those who resisted were sent into gulags or executed as enemies of the state.

It was hard to imagine so much blood spilled, so much destruction in the name of a glorious Revolution, as we picnicked in Peredelkino, the peaceful village where artists and writers had found a haven in the 1960s. Two men ambled past and Dima exclaimed, in the Queen’s English, as if an overenthusiastic tour guide, “Now you can see two writers walking by!” He paused. “They are talking about the weather!” We navigated past some generous dog crap on the path, and Dima exclaimed, “Perhaps we have come upon some prominent writer’s shit, right here on the sidewalk!”

I loved Dima’s cutting commentaries on writers. Unlike me, he didn’t put them immediately on a pedestal. For him, the writers who had bathed in the privileges of Soviet power deserved outright scorn. In his mind, they had relinquished their holy duty of preserving the conscience of Russia for vacations to Odessa and stable publication runs.

We visited Boris Pasternak’s house—replete with adoring gray-haired docent, who’d sit in the chair that Pasternak once wrote in, when no one was around, dreaming of her hero.

“This is where Boris Leonidovich,” she said, using his patronymic and sighing, sweeping her arm across the living room, “would play piano. And this is where Boris Leonidovich would sit and draw, when he tired of writing. And this is where—”

“—Boris Leonidovich hid from his guests, because of his sensitive soul,” Dima whispered to me. “One day, a man came down the path next to Pasternak’s dacha but didn’t stop. Boris Leonidovich came out and thanked him for not visiting.”

Oh to be loved the way this woman loved her Boris Leonidovich. Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago and his refusal to accept the Nobel Prize in Literature made him well known in the West, but he was also a tragic figure, whose sudden silence on a phone call with Stalin may have contributed to the death of Osip Mandelstam. The story goes that Mandelstam, who’d written a poem mocking Stalin, shared it with a small circle of friends including Pasternak. Someone reported Mandelstam to the government, and he was arrested and taken to Siberia, where he died. Pasternak tried to intervene, but when Stalin called him, he was unable to back his comrade. The very moment when his voice could have mattered, when he could have authored freedom for his friend, in his paralyzing fear, he could not speak.

A half-century later, all over the countryside, New Russians were buying up land and building preposterous dachas—not dachas as much as palaces. Just the other day, we’d passed one in Pravda built like an imitation church, replete with wooden cupolas. As quickly as this crass class and its own grandiose fantasies emerged, so did the jokes. A New Russian approached a girl and asked her to go out with him. She asked, “Well, do you have a two-story dacha?” “No,” he glumly replied. She asked, “Do you have a Mercedes-Benz?” No, he didn’t. Dejected, he went home and asked his old man what to do. “Oh, just knock a couple stories off your dacha, trade in your limousine, and you’ll be fine.”

They were more American than Americans, these New Russians, brash and unrestrained in their ardor for things to flash their shimmering accoutrements. Once, at the bookstore on Tverskaya, I spied a complete set of Arseny Tarkovsky’s collected works, in beautiful burgundy hardcover, and rushed for a place to change American dollars into ninety thousand rubles. I waited at the back of a long line at the bank, slowly approaching the front, then watched the teller leave for break, and a new line formed, without complaint, which I realized only too late. I began to sweat heavily, worrying that someone might take the Tarkovsky, a poet I loved whose books were almost impossible to find. At last, drunk on the possibility of this lucky purchase, I rushed back, the sweat pouring down my shirt as if I were my own rainstorm, and burst through the door. I clipped the eight-inch heel of an impeccably dressed, beautiful young woman, a paragon of New Russia, nearly toppling her. She’d been lingering in the doorway in the cloud of her unknowable, perfumed perfection, stylishly unconcerned with wanting poetry. I felt like Old Russia, panting and sweating for some old book, which still lay patiently waiting on the shelf. There would be no rush on poetry now.

In Peredelkino, we lounged about as if the whole country weren’t falling into ruin. “Honestly,” Natasha said, “everything seems upside down.” In July 1992, just a few months before, the ruble finally could be legally exchanged for dollars, and the rate of exchange went haywire, the ruble plummeting in value. Kids on the streets selling cigarettes made more money than their parents who had been toiling for years. While a tiny slice of the country was getting rich quick, most of the country lived far under the poverty line. By the end of 1992, inflation was over 2,500 percent. Older people lost their life savings overnight; more than that, with the fall of the Soviet Union, they had come to question the meaning of all their years of suffering. For a lifetime, they’d been waiting in long lines, often not even knowing what they were waiting for, just knowing that a line meant that something was bound to be ahead—and now just as they arrived at the front of the line, the store was empty, the doors were closing, and would not open again.

That fall, Russians began receiving vouchers for purchase of shares in state enterprises undergoing privatization. Even the word was foreign, vauchery, and people wondered if they were a scam, worth nothing more than toilet paper. Although they were said to be worth ten thousand rubles (about sixty-three dollars), people were buying them for as low as fifteen dollars in the metro. The people were naturally suspicious about state promises—and always in need of cash for the countless needs that the poor store away, the way that rich people store stocks and bonds—and so they sold their shares. This rapid privatization—with the unknowing support of the masses and the willing support of Yeltsin, who was known to install loyal supporters in soon-to-be formerly state-run industries—would make a precious few insiders so wealthy that we now know them as “the oligarchs.”

Sometimes I still dream that I am back in Moscow, running up to Russians in lines to sell their vouchers, trying to convince them to hold onto them, but either my voice makes no sound and they can’t hear me, or I’m invisible, or they simply don’t believe me, and anyway, there were bills to pay, because someone needed surgery, because someone needed to replace the tires on the Moskvich, because someone was getting married, the catalog of becauses unfurling toward the horizon.

Dima hated what was happening in Russia, and sometimes he blamed America.

One night, in the Den of the Voice, he seemed particularly irritated.

“Have you seen that Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum sign at Pushkin Square?” he asked one day, shaking his head.

Spearmint Gum sign. Photo: Philip Metres

The gigantic bronze statue of the great poet, whose head bent downward in humility toward his feet, stood just across Tverskaya from the first McDonald’s restaurant. Around the great buildings that surrounded the square, billboards had begun to crop up, selling the latest American products: Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum, Calvin Klein, Mars Bars.

“It’s disgusting,” he spat.

He thought it was a desecration, the war of American culture on Russia. It made it all the harder that his own son, also named Phil, craved Wrigley’s gum. Russians craved American products because they seemed like keys to a freedom that had so long been denied to them. Yet I could hear the pain in Dima’s voice. I understood disliking the crassness of commercial culture, but I had no idea what it might feel like to someone who saw these signs as weapons in an arsenal meant to destroy what was good about Russia—not its own zhvachka, its chewing gum, necessarily, but its distinctiveness, its independence from the West. They could no longer write their own destiny.

I tried to commiserate, but in Dima’s eyes, I was an heir of the free market, whatever my interest in Russian poetry. And, to be honest, I found the juxtaposition of Pushkin and Wrigley’s delicious. Plus, when the new Pizza Hut opened—literally a window in the wall of a building just down the street from Pushkin—I was delighted to be able to taste some good old American pizza. I kept that delight to myself around Dima.

“Someday you’ll understand, when America falls,” he said.

I shook my head and laughed.

I thought he was crazy. They’d lost the Cold War, and their system had gone bankrupt—economically and morally. Yet Russian culture, hidden and sometimes lost beneath the steamroller of Soviet culture, was lost again in the blind rush for things American. I’d come to study Russian poetry, and it was harder and harder to find the work of contemporary poets. When we went to interview the poet Nikolai Tryapkin, one of Dima’s heroes, he told us that “before, I knew my talent was needed though they didn’t let me publish. Now, no one needs poetry, mine included.” While the West was starved for poet-martyrs that proved the evil of the Soviet Union, now no one—Russians included—seemed to be thinking much of poetry. Censorship did not kill Russian poetry, but it seemed like capitalism and the free market might.

But Dima would not let poetry die quietly. He’d whip himself up into a frenzy and froth, reading a poem by one of the Russian greats, as if the poem had found the animal in him and loosed it from its tethers. I would watch, the way a child looks at a snorting horse in a corral, not sure if he’d ever want to hold out his hand to pat its formidable head.

Censorship did not kill Russian poetry, but it seemed like capitalism and the free market might.

Russia may have been a pathless wood for me, and Dima was Virgil to my Dante, showing me the way through. But this country of toppled statues and broken-down hopes wasn’t hell. Russia was like every other place on earth, at once heaven and hell, its delights and torments all wound together. Dima taught me what happens between cultures, between languages, balancing on the wire of poetic lines over the abyss between us, between Russia and America.

More than that, Dima became my older brother, bringing me on the bus to an open-air market in the zero-degree cold of December to buy a real Chinese winter coat, when my ridiculous American dress coat turned out to be worthless against the cruelty of Russian winter.

“That’s your coat?!” he said, his breath visible in the arctic air. He shook his head at my cashmere coat that opened so generously at the neck—as if it were designed to show off the suit, shirt, and tie underneath.

“Yes, it is,” I said, feeling stupid, breathing my own frost.

He was delighted by my idiocy, but even more delighted to help me.

For the rest of the winter, I donned a puffy-down red and black coat that made me look like a real-life matryoshka.

As the cold set in, even the Den of the Voice’s oven would not keep us warm. But we tried anyway. In the smidgen of his kitchen, where only one person could move around, I would sit and watch Dima whip something up out of nothing, defying the laws of physics. From tins of cracked and hardened sugar and flour and a bag of apples, he’d produce a sweet apple cake that, to this day, I can still taste. I’d bring along a Snickers bar and split it with him, sharing the sweetness of American mass production. Even if the chocolate was second-rate, as if they’d added wax to the cocoa, it was a reminder of home.

We were a study in contradiction. Dima, who in his fever for Russian literature, his passion for the Russian Idea, the idea of Russia’s unique destiny, who found the Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum billboard above Pushkin Square to be an obscenity, also loved the Beatles and Syd Barrett and Bob Dylan. I, who wanted to live like a Russian but could barely stomach the fish and sauerkraut that Russians were eating for breakfast, translated Russian poems into English between bites of a Pushkin Square Big Mac.

In the Den of the Voice, through that bitter winter, we lay on couches across from each other, wearing our winter hats and stacks of fragrant blankets. One night, as a lesson with a dollop of humor, he dropped the phonograph needle to “Trepak” by Modest Mussorgsky, featuring the bass of Fyodor Shalyapin: “In the darkness / Death is hugging and caressing an old man.” The old man, a peasant, slowly freezes to death. Death coaxes him to let down his guard, whispering to him: “Lie down, curl up and fall asleep, my dear! / I'll warm you up with snow, my darling.” As he loses consciousness, he begins to dream of summer fields, the sun laughing, songs hovering in the warm air. As I dreamed all winter of mowing the lawn, of girls wearing tank tops, and, at a hot beach, of leaping so high that I was flying.

In the obdurate cold, I felt as if I were partly living inside Dima’s poems—how life gets pared down to its primal need:

We have nothing, dear Lord.

Nothing has come to us,

Just this spare winter light.

Can we see our faces

There – still-wet, blurred-white

Pigment, as if, risen

From this our earth-prison,

Awaiting judgment’s word?

From the millstones of heaven

Snow-silence spills and spills.

Why must the shallow cup

Of this vale become so full? (Image 94)

One evening, walking to the Den of the Voice, twilight falling all around me, I had this feeling that I was yet again sinking further into this country, that I was finally understanding it and my place in it. When I reached the apartment building, in the dark, I followed Dima into the foyer. The hallway was absolutely pitch-black, and what I thought was the wall opened into another space of dark—the interior foyer. Dima fumbled with the keys, feeling for the lock, and I suddenly felt that my whole life was a string of such doors.

I’d long stopped writing poems, and even my daily journal had gone silent. I’d come to learn Russian poetry partly to learn how to write my own, but language utterly failed to describe this place.

By January, midway through this journey of strife, something had changed. Dima’s view of Russia—embittered by the madness that had descended into his civilization—began to eat at me. I’d long stopped writing poems, and even my daily journal had gone silent. I’d come to learn Russian poetry partly to learn how to write my own, but language utterly failed to describe this place. Russia was bigger than my words for it. As much as Dima had guided me, I’d come to the place where I needed to go alone. I’d just have to find the words to tell him thank you and I’ll never forget this and goodbye.

Taking a break from translations, Dima made a split-pea soup from a package of dried ingredients. Within minutes of eating, my stomach started to convulse. I rushed into the tiny bathroom and retched all over the tub, painting its off-white with yellow-green.

Dima hovered close by, wiping the sweat from his forehead, worried that he was the author of my suffering.

My stomach would not rest until it was completely free.

John Carroll University