Editor’s Note

[Borges’s] Argentinians act out Parisian dramas, his Central European Jews are wise in the ways of the Amazon, his Babylonians are fluent in the paradigms of Babel.

– Anthony Kerrigan, introduction to Ficciones

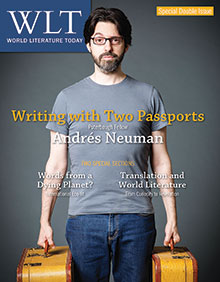

The issue you hold in your hands is actually two in one: our regular May issue, in the pages of which we had planned on featuring international eco-literature (page 69), as well as our July issue, which we were going to devote to the topic of translation (page 45) and to the work of Andrés Neuman (page 89). Circumstances beyond our control forced us to combine the two (or three) ideas into one, so we expanded the issue to 128 pages in order to fit (almost) everything inside.

The conjunction of Neuman and translation turned out to be a natural pairing. Some of the most brilliant perspectives on translation have been written in the Spanish language, including José Ortega y Gasset’s “The Misery and Splendor of Translation” (1937) and Octavio Paz’s Traducción: Literatura y Literalidad (1971). One of my personal favorites is Jorge Luis Borges’s “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote” (1939), from the collection Ficciones (1956; Eng. 1962). Menard, a turn-of-the-century French symbolist poet, sets out, not merely to copy Cervantes’s famous novel, but to compose “the Don Quixote” in a language not his own, as if the original were “unnecessary,” “accidental,” “a book not yet written.” We know that chivalric romances addled Don Quixote’s brain; after Menard’s preposterous (indeed, quixotic) Quixote, we can never look at the prospect of “translating” an original in quite the same way.

In the cosmopolitan tradition of Borges, we now have two fascinating new commentaries on translation by another Argentine-born writer, Andrés Neuman: a micro-essay on translation, “Translating Each Other” (one of the most popular blog posts we’ve ever published), in which we learn that what the translator “ultimately receives is a lesson about his own language,” and “Writing with Two Suitcases,” the 2014 Puterbaugh lecture featured in this issue. In the latter, Neuman situates his very existence in between two homelands, Argentina and Spain, as a type of translation: “When immigration alters directly the use of that very language that we consider our own,” he writes, “what becomes uprooted is the foundation of speech with ourselves. . . . Immigration inaugurated a certain intimate conflict with my own language. A foreignization of my native tongue. . . . To communicate with my new classmates, I spent my adolescence mentally translating from Spanish into Spanish. . . . Over time, this doubled learning ended up being the only possible way to approach my language.”

I find it brilliant that the many types of translation—intralingual, interlingual, and intersemiotic, in Jakob-son’s famous typology—are embodied in Neuman’s work. Intralingual, at the level of “Spanish into Spanish”; interlingual, in Neuman’s own work as a translator from German and English into Spanish; and intersemiotic, in the case of Neuman’s poetry being set to music (Alguien al otro lado), which can also take the form of parables being transposed into paintings, or the transformation of literary works that are adapted into theater, dance, and film. Like Proust and Nabokov, Neuman understands that translation is “consubstantial with the act of writing” (to use Antoine Berman’s phrase), and that the task of the writer is a creative act of translation.

Before his visit to the University of Oklahoma, we were all wondering how we should pronounce Neuman’s last name. When we asked Andrés, he told us it doesn’t really matter: it could be with a German accent, Noy-mahn; with a French accent, Neu-mohn; a Spanish accent, Ney-oo-mahn; or an English accent, New-man. For readers interested in the mysteries of naming, the misery and splendor of being a writer, and the beautiful betrayals of translation, there’s no better place to start than the work of Andrés Neuman. (Dozens of photos from the Puterbaugh Festival can also be found onWLT’s Flickr page, and a video highlights reel appears on the festival website.)