Indigenous-Minority Poets from China: 15 Recordings for International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples

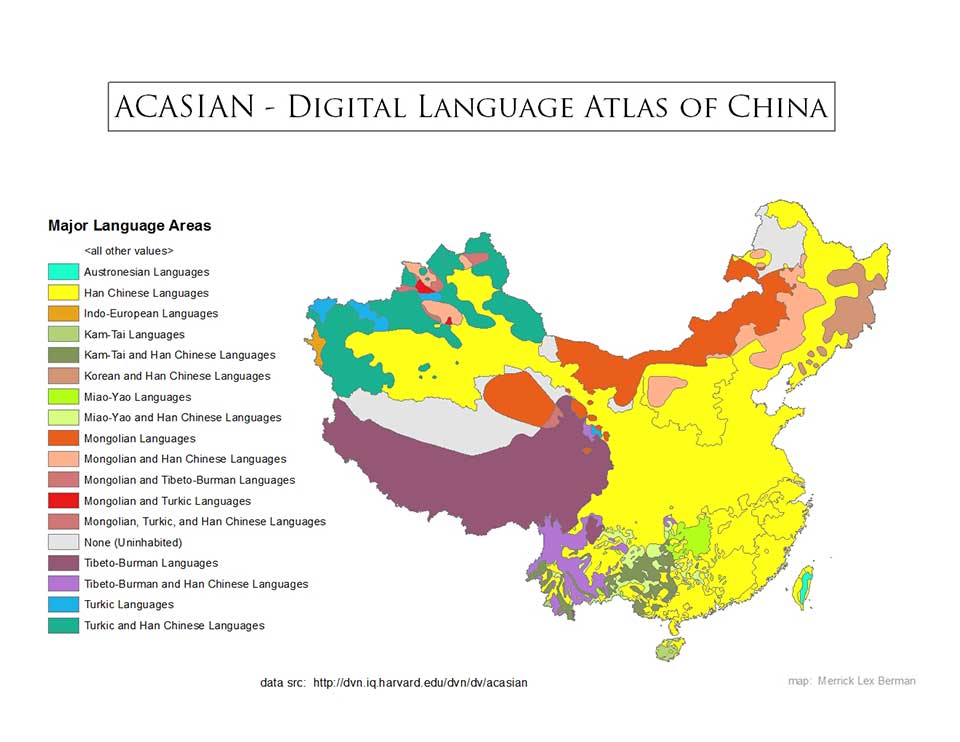

To celebrate the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples on August 9, I invited fifteen Indigenous-minority poets from China to record their readings of their own short poems in their Indigenous-minority mother tongues. Most of the languages presented here are endangered. Some may be never heard of, such as Dagur, Yugu, Bonan, Nu, Derung, Lahu, and Mulao, even for people inside China. I have arranged the poets/languages geographically in a counterclockwise order: from Northeast to Northwest, down to Southwest, South, and up to the Southeast-East coast of China. All the authors are bilingual in their native Indigenous-minority languages and Mandarin Chinese. Some are even biliterate. Two of them are singer-lyricist-musicians who speak rare languages and who promote their mother tongues to a larger audience than what poets could ever reach.

Here is a list of the authors by name, year of birth, ethnicity, and province/region:

1. Wu Yingli (b. 1967), Daur from Inner Mongolia

2. Ha Mo (b. 1973), Dongxiang from Gansu

3. A Marjen, Yugu from Gansu

4. Ma Xuewu (b. 1972), Bonan from Gansu

5. Kulaxihan Muhamaitihan (b. 1974), Kazakh from Gansu

6. Abiba Yiminjan (b. 1975), Tajik from Xinjiang

7. Yomqung Sangmo (b. 1998), Tibetan from Ngari, Tibet

8. Pema Yangchen (b. 1974), Tibetan from Shannan, Tibet

9. Danba Wangmo (b. 1991), Rgyalrong Tibetan from Sichuan

10. Liu Wenqing (b. 1984), Nu from Yunnan

11. Gao Qiongxian (b. 1986), Derung from Yunnan

12. Lal Vet (b. 1988), Lahu from Yunnan

13. Gebu (b. 1964), Hani from Yunnan

14. Tong Yu (b. 1978), Mulao from Guangxi

15. Lan Yongxiao (b. 1982), She (Shan Ha) from Zhejiang

Wu Yingli, originally from Ergun, the northeast tip of Inner Mongolia, currently works in Beijing as a literary publisher. She says Daur poetry uses alliteration frequently and Daur people have a long history of oral literature such as epics and Ulgir (folktales).

Four poets from Gansu province, the historical gateway to the West for Chinese as well as the ancient route to enter inland China, speak four distinctively different languages.

Abiba Yiminjan from Pamir of Xinjiang writes poetry in Uyghur only, but she has read a poem in her mother tongue, Tajik, upon my request.

This is part 4 of the video anthology of “Indigenous-Minority Poetry from China,” and several Uyghur poets appear in the earlier parts. Poet-translator Dilmurat Talat from Xinjiang has told me that 90 percent of the poets in Xinjiang write in non-Chinese languages nowadays, and he translates their work from Uyghur, Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Tajik into Chinese.

For Tibetan poets, in earlier parts of the video collection, I have showcased poets from Lhasa, Back Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, and Sichuan speaking dialects that are not mutually intelligible such as Ü-Tsang Tibetan, Amdo Tibetan, and Kham Tibetan. This time, I was trying to go beyond the three major dialects of Tibetan. Yomqung Sangmo is a schoolteacher from Ngari, Tibet, a very remote area in China, bordering India, Nepal, and Kashmir. Her Tibetan sounds very close to the standard Lhasa Tibetan except the tones, according to my informant Tenzin Pelmo from Lhasa. To trace the language of the ancient Zhangzhung Kingdom in Ngari, I found Danba Wangmo, a Rgyalrong Tibetan from Sichuan. She talks about the difference between standard Tibetan and Rgyalrong Tibetan, which is extremely interesting. Zhangzhung people migrated to today’s Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan province around the eighth century. They have maintained the ancient consonant clusters that are lost in modern Tibetan. It is so informative and revealing that it’s included in this video collection as the only nonpoetry piece. Rgyalrong could be the linking language between Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan languages, if we see languages around the world as a continuum separated due to isolation after migrations.

Rgyalrong could be the linking language between Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan languages, if we see languages around the world as a continuum, separated due to isolation after migrations.

There are four poets from Yunnan, the most diversified region in China, culturally and linguistically. They speak “small” minority languages compared to the “big” languages such as Tibetan and Uyghur. The video clip of Gebu’s live reading performance is invaluable. He is a strong promoter of Indigenous poetry in the Hani language. We can see his poem in Hani (in the new romanized writing system) as projected onto the screen behind him.

Tong Yu from Guangxi reads her poem in Mulao (Mulam), another rare language in the Indigenous-minority communities in China that’s unique to Guangxi in southern China, belonging to the same language branch as Zhuang and Dong (kam) (see part 2 of the video anthology).

Last but not least, Lan Yongxiao promotes his She (Shan Ha) language by singing songs in the She language. He says his ancestors’ stories are carried on only in songs, and he will do the same. He is a migrant worker–turned–popular singer from the east coast Zhejiang. He said fellow workers from his tribe had low self-esteem working in big cities because of their ethnic minority status and their tribal language. He is proud of his Indigenous-minority identity and the oral literature of his She tribe. He says if young people don’t speak She, the cultural heritage of She can never be preserved.

If young people don’t speak She, the cultural heritage of She can never be preserved.

I have learned so much from the Indigenous-minority poets, their cultures and languages. For instance, the tattoo-faced Derung (Dulong) women and their weavings, the terraced rice fields that Hani people have created on the mountains by the Red River in Yunnan, the four dialects of Dagur language by Daur people in four different locations in northeast and northwest China.

To me, not only is it invaluable that poets and lyricists can save endangered languages through poems and songs but also, or even more so, that the uniqueness of the Indigenous-minority languages have enriched and revived poetry in general.

Chrystal Ho and Al Lim from Singapore have co-translated five of the poems per my invitation. Hmong poet Xi Chu and Tibetan poet Tenzin Pelmo have helped with inputting subtitles into some of the videos.

It’s been an exciting experience working on Indigenous-minority poetry in China and trying to figure out how the languages are related and separated by time (different times of migration) and place (different routes of migration). Tracing back, I see how humans have survived in extremely harsh environments, mountains after mountains. Each language is a lookout to observe a new world.

Earlier parts of the “Indigenous-Minority Poetry from China” series can be found on the lyrikline blog.

Los Angeles

Editorial note: WLT’s September issue will showcase “Indigenous Literatures of the Americas” with contributions by sixteen Native writers from the “long, long continent” of the Western Hemisphere, many presented in bi- or trilingual versions online with audio recordings by the authors.