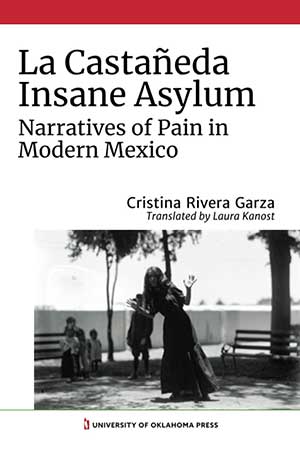

The Patients Talk Back: Contested Narratives in Cristina Rivera Garza’s La Castañeda Insane Asylum

Men in finely cut suits and women in elegant dresses gather before a gate suspended between massive stone columns adorned by giant floral sprays. Tricolored flags fly above and alongside a sign atop the gate that reads “Manicomio General.” This scene appears in a photograph of the September 1, 1910, opening celebration of the Castañeda General Insane Asylum in the small town of Mixcoac, just outside of Mexico City. Within weeks the Mexican Revolution begins. Less than five years later, in February 1915, Zapatistas briefly occupy the asylum while fighting against the Constitutionalist army. The battles add fear and chaos to the already chronic overcrowding, understaffing, and food shortages the asylum’s patients suffer. As Cristina Rivera Garza recounts in La Castañeda Insane Asylum: Narratives of Pain in Modern Mexico (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020), whose pages include the opening-day photograph, the social welfare institution inaugurated in 1910 required decades of preparation by doctors, engineers, lawyers, social workers, and politicians. The efforts and general social context that made possible the asylum’s construction included reports on how psychiatric medicine was practiced abroad; the first courses on psychiatry taught in Mexico City’s School of Medicine, in 1890; the purchase of land on the capital city’s outskirts; the construction of twenty-five buildings for medical, administrative, and custodial staff and for housing and isolating patients with different diagnoses; and the gradual shift to state-sponsored mental health care from its traditional, centuries-old supervision by the church.

Men in finely cut suits and women in elegant dresses gather before a gate suspended between massive stone columns adorned by giant floral sprays. Tricolored flags fly above and alongside a sign atop the gate that reads “Manicomio General.” This scene appears in a photograph of the September 1, 1910, opening celebration of the Castañeda General Insane Asylum in the small town of Mixcoac, just outside of Mexico City. Within weeks the Mexican Revolution begins. Less than five years later, in February 1915, Zapatistas briefly occupy the asylum while fighting against the Constitutionalist army. The battles add fear and chaos to the already chronic overcrowding, understaffing, and food shortages the asylum’s patients suffer. As Cristina Rivera Garza recounts in La Castañeda Insane Asylum: Narratives of Pain in Modern Mexico (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020), whose pages include the opening-day photograph, the social welfare institution inaugurated in 1910 required decades of preparation by doctors, engineers, lawyers, social workers, and politicians. The efforts and general social context that made possible the asylum’s construction included reports on how psychiatric medicine was practiced abroad; the first courses on psychiatry taught in Mexico City’s School of Medicine, in 1890; the purchase of land on the capital city’s outskirts; the construction of twenty-five buildings for medical, administrative, and custodial staff and for housing and isolating patients with different diagnoses; and the gradual shift to state-sponsored mental health care from its traditional, centuries-old supervision by the church.

The narrative of order and progress that characterized the regime of Mexican president Porfirio Díaz was interrupted by what was to become another dominant narrative, the revolutionary legacy and its institutionalization in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. Before the asylum closed in 1965, changes in scientific narratives about individual and collective mental health shaped the daily lives of the thousands of inmates who lived there, many for extended periods of time. For example, Rosario E. (as is the case with all individual patients mentioned in the book, her actual name is not revealed) lived in confinement for sixty years. In 1896 she was admitted into the Divino Salvador asylum, which dated to the late seventeenth century. In 1910 she was one of hundreds of inmates transferred to La Castañeda from older institutions. Despite their fragile and fleeting position in relation to all the forces that made the asylum possible, inmates’ stories were hardly the simple products of dominant narratives that imposed themselves on precarious subjects. Rivera Garza’s fascinating and thoroughly researched study documents, on the contrary, how transcribed statements and examples of their own writing make it clear that patients contested and sometimes guided the relentless attempts to define them made by doctors, nurses, judges, police officers, and family members. Originally published in Spanish as La Castañeda: Narrativas dolientes desde el manicomio general, 1910–1930 (Tusquets, 2010), Rivera Garza’s text is now available to English-language readers in Laura Kanost’s excellent translation.

Rivera Garza’s fascinating and thoroughly researched study documents . . . the relentless attempts to define the patients made by doctors, nurses, judges, police officers, and family members.

Among the patients most vulnerable to physical and discursive violence were women, including Modesta B., whom readers of Rivera Garza’s Nadie me verá llorar (Tusquets, 1999)—translated into English as No One Will See Me Cry: A Novel (Curbstone, 2003)—will recognize and misrecognize as Matilda Burgos, the novel’s protagonist. I say misrecognize because La Castañeda emphasizes the danger that lies in making the claim of entirely recognizing another. Fear of women and the socially and clinically sanctioned misrecognitions of their sexuality and the consequences of domestic abuse lie at the foundations of psychology and psychiatry. Rivera Garza finds the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century diagnosis of moral insanity to be especially emblematic of this tendency. She writes that it was used “to explain female behaviors that violated implicit gendered rules of propriety (decencia) and domesticity.” As a response to the power embodied in their exclusively male doctors, actively contributing to or resisting their diagnoses was especially important for women. Rivera Garza writes that women’s own narratives about treatment and confinement, included in their case files, allowed them to “describe the complex nature of their condition—its physical and spiritual causes, its evolution and social representation” and to become “their own authors as legitimate, albeit disconcerting female citizens of the new era.” Narrative competition and misrecognition applied to male inmates as well. Rivera Garza cites a transcription from Marino García’s readmission interview in 1941 (he was originally admitted in 1919 and released in 1931) that includes several observations as puzzling as the following: “Yesterday I saw an Arab up in the air, up in the sky, where the bombs explode. I have not died from the bullets because my Father, who is Eternal, told me that I would be eternal too.” The clinical history turns this fantastically suggestive and idiosyncratic discourse into a categorical diagnosis of an illness that is likely to be paraphrenia and that bears no apparent association with syphilis. To say the least, the diagnosis leaves the reader wanting. Acknowledging such a want but refusing its easy satisfaction is a primary tenet of Rivera Garza’s book.

As a response to the power embodied in their exclusively male doctors, actively contributing to or resisting their diagnoses was especially important for women.

In general, competing and contested narratives, and efforts to domesticate them, shape and sustain archives. La Castañeda is based on one specific archive while forming part of another. On one hand, the book is the result of Rivera Garza’s adaptation of the doctoral dissertation she completed in the mid-1990s, which entailed conducting research in the asylum’s archive of 75,000 case files. On the other hand, it forms part of the archive made up of Rivera Garza’s related works of fiction and nonfiction, which feature competing narratives and the gender-based politics that shape their meaning. In addition to the novel No One Will See Me Cry, two other works of fiction stand out: La muerte me da (Tusquets, 2008) and La cresta de ilión (Tusquets, 2004), translated into English as The Iliac Crest (Feminist Press, 2017). Muerte is about a female detective, a female professor, and their encounters around a series of murders involving castration. It also includes a lengthy meditation on the differences among forensic writing, poetry, and prose. Iliac tells the story of a hospice doctor’s attempts to deal with the unannounced visit of an actual writer, the outstanding Amparo Dávila, who, he fears, somehow threatens his masculinity. Regarding nonfiction in Rivera Garza’s archive, the essay titled Los muertos indóciles: Necroescrituras y desapropiación (Tusquets, 2013)—translated into English as The Restless Dead: Necrowriting and Disappropriation (Vanderbilt University Press, 2020)—values collaborative literary production in an age when sole claims to authorship, Rivera Garza argues, are insufficient for navigating the violent Mexican present.

Collectively shaped and competing narratives in La Castañeda appear most concretely in relation to the case files that Rivera Garza cites and works from. Writing about her transformation of the patient Modesta B. into the character of Matilda Burgos, Rivera Garza’s unresolved want takes the form of the questions that multiply every time she looks at the original file. For example: “Was she really the one who said that her mother had been murdered? Did she deal with Bolsheviks and anarchists like her writing in her ‘diplomatic dispatches’ implies? [. . .] How did she look at the doctors who insisted on making her speak?” Acknowledging the fact that some questions remain unanswerable is a historian’s responsibility, Rivera Garza argues, as is belying the oft-repeated and deceptive gesture of giving voice to the past.

The doctors at La Castañeda, Rivera Garza is careful to point out, were not one-dimensional embodiments of threatened power, responding by imposing their voices onto their patients’ lives. Many listened carefully to their patients, and their notes about or transcriptions of patients’ words in case files are the result of a collaborative, though very uneven, effort to make connections among symptoms, society, and domestic life. As part of this process, patients “strove to relate their illnesses to the suffering that was invading their lives, giving them pain and meaning at the same time.” Rivera Garza demonstrates how this combination of pain and meaning emerged in tandem with central developments of Mexican modernity, including psychiatry, criminology, and two related forms of documentation: the inmate’s psychiatric interview and the admissions photograph. Fields of study and the instruments and methodologies their experts employ risk silencing those they are purported to understand better and help. When Rivera Garza writes that those diagnosed with mental illness “spoke from the other side of progress,” she opens up the possibility that narratives of progress, which include the paradoxically institutionalized revolution that defined Mexican politics for decades, might be more insane than those who were confined in order to safeguard ostensibly normal people.

Fields of study and the instruments and methodologies their experts employ risk silencing those they are purported to understand better and help.

The chapter dedicated to photography bolsters its overall warning against aspiring to total recognition, an aspiration that undergirds dominant discursive insanity. Associated early on with phrenology and other ways of reading a subject’s apparent deviance, the questions that patients’ admissions photographs continue to raise far outnumber any answers they may ever provide. Consider the photograph of the patient featured on the cover of La Castañeda. She holds up her hands and looks at the photographer while other out-of-focus figures witness the moment her photo is taken. The patient’s hands are on either side of her body at shoulder level, the palms facing forward. The pose reproduced photographically from a long-disappeared instant of her life suggests neither a warning nor an invitation to the photographer, the viewer, or Rivera Garza’s reader. Instead, it creates a sense of horizontal movement that is related more clearly to her immediate surroundings, the daily life of the asylum landscape, which continues to appear in the frame while forever lying beyond it at the same time.

University of Maryland

Editorial note: Rivera Garza’s “On Our Toes: Women against the Femicide Machine in Mexico” appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of WLT.