See How She Creates Light: On Translating Liu Xia

I was struck by one of the poems Liu Xia released a few days before her husband, Liu Xiaobo, died of cancer as a political prisoner in China. One line in particular hovered in my dreams until one morning I woke up with this translation: “(I wish that I, astonished, would glow) my body / in full bloom of light for you.” I wrote it down quickly: my body in full bloom of light for you. Liu Xia foresaw herself saying goodbye to Liu Xiaobo by casting a thousand beams of light as he set off on the “Road to Darkness” alone. I’ve revised other parts of the poem many times but never changed a word in this: my body / in full bloom of light for you. The Chinese original is actually much shorter, “light blooms” literally, but the action of blooming seems to be repeating like a slow-motion scene. Now that I look at the poem again (in her handwriting), I’m tempted to use “burst into light,” but the light initially came to me in the form of flowers as Liu Xia used the verb “bloom,” an unusual word for grieving, but it’s exactly this word that brought tears to me again and again.

At the sea burial that the whole world watched, the only thing she was allowed to do was to spread flower petals into the sea as if leading the way for Liu Xiaobo’s soul to travel in the water. Liu Xia even predicted the sea when she wrote “Story of the Sea” in 1982. So did Liu Xiaobo when he wrote “Facing the Sea Alone” in 1994. Is sea his destiny? In 1986 Liu Xia wrote about being a footnote to someone. She imagined talking with a half-imagined woman by the name of Camille Claudel, an artist she admired whose life got intertwined with hers. And she called her “Stranger” and drank a cup of Chinese liquor with her. Yes, it was a strange role for her to be the wife of a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. “It takes energy to be a long footnote”—they met in 1982, married in 1996; she spent more than half of their time alone when Liu Xiaobo was in prison numerous times, and became his widow in 2017. “What a footnote!”

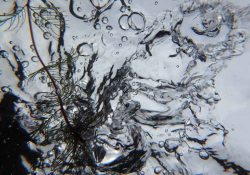

Equally and even more touching were her black-and-white photographs entitled Lonely Planets that appeared on the Internet shortly before Liu Xiaobo’s tragic death—dark backgrounds with aluminum foil in the shape of balls (i.e., stars). Liu Xiaobo walks in the sky, another world, above us, searching for light and giving us light. To create the light, Liu Xia uses aluminum foil that shines in the dark. In another series of photographs, she has used cloth that absorbs light. “In the shadow, I sew a bedsheet / so clumsily, as if sewing my entire life, / all embedded, / into the bedsheet that can only wrap my body. / Nobody hears the cries / of a soul / in the stitches.” The cries have become flashing light in her photography and her poetry. And in her painting Tree as well, reproduced here: see how light moves around the tree, how some twigs are about to take flight in a burst of cries.

I was in The Hague in June 2017 to visit art museums. Looking at Vermeer’s work closely, it dawned on me that light in his paintings was not natural but man-created: there was an inner window where light radiated in. See how the lines become rhythms? And here in Liu Xia’s poems, see how the words become light. But how do we transform the light into another language? What do we really do when we translate a poem? First we enter the original and feel its light. For the translation to be effective, it has to illuminate, too: words need to be clear and precise, penetrating things as light does and creating a pathway for the meaning to come through. But I’m often pessimistic about translation. Good lines come to me occasionally, and usually all of sudden, as if bestowed. To make the rest of the poem work, it takes endless revisions. Everything works around that central line, serving it and yielding to it. And everything becomes a footnote to the line that gives light. And the translator becomes a footnote to the author. “It takes energy to be a long footnote.”

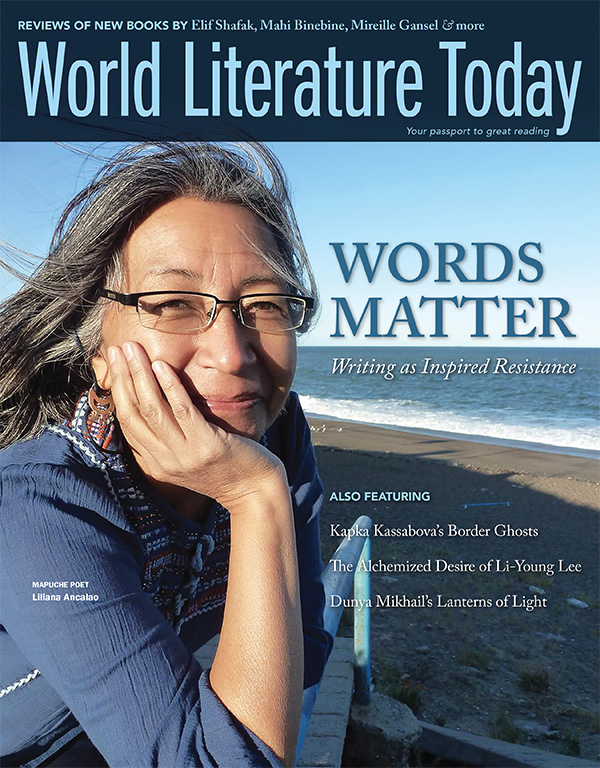

Finishing Empty Chairs: Selected Poems by Liu Xia seemed to have merely started a journey of which it was just the beginning. It’s through translating Liu Xia again that I see how much lies ahead. Liu Xia has a rich body of poetry spanning from 1982 to the present, witnessing the political and social changes in China as well as the changes in her personal life: falling in love with a dissident writer, accompanying him during his long years of imprisonment by staying in China, standing firmly with him, her life forever changed by his. One has to have gone through the political reality in contemporary China from the 1980s to the new century in order to understand just a little bit of her work, even though she is nonpolitical.

Poetry is an art seen better in the light of political events, but at the same time the artistic aspect of her poetry sheds light on how we see the political situation in China. It’s the uttermost responsibility of a translator to bring that artistic light to the forefront. I feel empowered by the light Liu Xia has created in her poetry, but I wish to be winged to come to the same height to see what she sees.

For more, read two poems by Liu Xia.