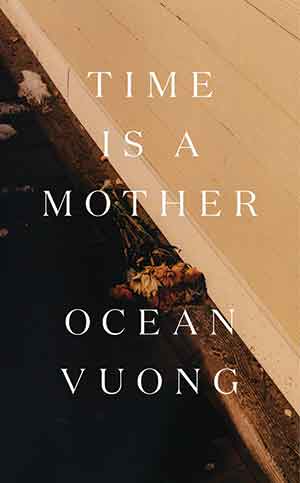

Time Is a Mother by Ocean Vuong

New York. Penguin. 2022. 128 pages.

New York. Penguin. 2022. 128 pages.

TIME IS A MOTHER is Ocean Vuong’s second poetry collection and his first book since 2019, when the award-winning novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was published and Vuong received a MacArthur Fellowship. In Time Is a Mother, Vuong, thrity-three, born in Vietnam and raised in hardscrabble Connecticut by his illiterate mother, Hông (she went by Rose), expertly picks up familiar themes—self-discovery as a gay man, the legacy of war, how language is both garden and minefield—while also presenting more abstract, challenging material. The result is mostly successful.

The book is divided into four sections, all of which address Vuong’s grief after his mother’s death from cancer. The first section is preceded by a stunning prologue, “The Bull,” rich with surreal imagery and evocations such as “needing beauty / to be more than hurt gentle / enough to want” that gesture at the desire and intense fragility present throughout the collection.

The first and fourth sections are arguably the least engaging. “Dear Peter” is a predictably melancholy epistle to a partner written while hospitalized, while “Skinny Dipping” is a sensual double entendre about leaping from a bridge into the water below that gets lost in its own descent:

some boys

have ghosted

from this high

but I wanna go

down on you

anyway to leap

from the bridge

I’ve made

of my wrongs.

Confusing descriptions of flight continue in “Beautiful Short Loser”: “I’m on the cliff of myself & these aren’t wings, they’re / futures.” Vuong’s attempts to capture the fraught feelings of attraction, diversion, and grief are earnest but underdeveloped. Even “Dear Rose,” which describes his mother’s journey from wartime Vietnam to immigrant life in the US, verges on being incoherent. So many potent and recurring symbols—bullets, ants, anchovies, flowers —vie for significance that they muddle the poem.

In the first and fourth sections, only “American Legend,” a wry recollection of a father, son, and dog in a car crash, is refined enough to be compelling:

he slammed

into me &

we hugged

for the first time

in decades. It was perfect

& wrong, like money

on fire.

These lines are violent and vulnerable but also biographically fictitious, since Vuong’s father was absent. “I did it to hold / my father, to free / my dog,” writes Vuong. “It’s an old story, Ma. / Anyone can tell it.” The occasion of losing one parent inspires mythmaking about the other, already lost.

The second and third sections, however, are a triumph. In “The Last Prom Queen in Antarctica,” the protagonist is “not a writer / but a faucet underwater.” “It’s true,” they continue, “I saw a boy / in a black apron crying in a Nissan / the size of a monster’s coffin & knew / I could never be straight.” Such vignettes depict the drama, dignity, and discovery possible in the most quotidian moments in blue-collar American life.

The third section contains two poems, the longest and most memorable of which is “Künstlerroman” (German for “artist’s story”). The poem depicts a kaleidoscopic range of events, from the attacks of 9/11 to domestic scenes in the protagonist’s own life, all in reverse. The Twin Towers “reassemble,” and birthday cake candles reignite in front of a child’s lips, as though to solve Proust’s dilemma: only through language is time retrievable. And, of course, so too is Vuong’s departed mother resurrected through tender verse. The exercise might feel like a party trick if attempted by a less adept writer, but Vuong suffuses the montage with a powerful lyrical longing. Overall, such exquisite articulations of longing and grief sustain the collection.

Peter Krause

New York

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!