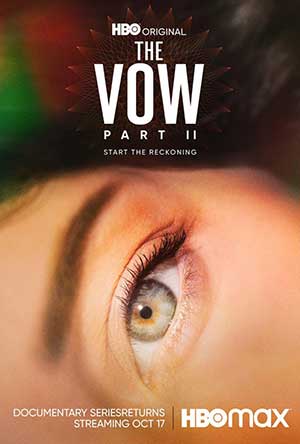

The Vow: Trials within Trials

A writer’s time attending the theatrical trial that became the docuseries The Vow leads him to reflect more generally on the culture-wide moral relativism and abuse of language that allow a cult leader to inflict his damage.

Watching HBO’s hit docuseries The Vow (season 2), I am transported back to New York, three years ago, where I was invited to cover the trial of cult leader Keith Raniere. Since cameras were not permitted to record the proceedings, my role as a courtroom writer, in this deeply disturbing and salacious high-profile case, was to act as something of a sketch artist with words. Not merely to document what was being said, since there were transcripts for that, but rather to try to read the room and draw out the subtext.

Watching HBO’s hit docuseries The Vow (season 2), I am transported back to New York, three years ago, where I was invited to cover the trial of cult leader Keith Raniere. Since cameras were not permitted to record the proceedings, my role as a courtroom writer, in this deeply disturbing and salacious high-profile case, was to act as something of a sketch artist with words. Not merely to document what was being said, since there were transcripts for that, but rather to try to read the room and draw out the subtext.

Every day, before the trial commenced at 9:30am, those of us inside the courtroom were treated to a picturesque sight. Seated in the front row, one of the court artists—an elderly, diminutive woman with long, silvery hair and twinkling eyes—would ceremoniously blindfold herself. Wrapping her scarf around her eyes, she would sit still this way, perhaps, steeling herself for a fresh batch of horrors. By association, I’d recall that justice is depicted as blind. Maybe the artist’s evocative gesture was an acknowledgment that insight is stronger than sight, and truth requires meditation. Whatever the case, it was an arresting sight, befitting this theatrical trial.

Seated in the front row, one of the court artists—an elderly, diminutive woman with long, silvery hair and twinkling eyes—would ceremoniously blindfold herself.

Think of a particularly tense family reunion. Amplify that by many orders of magnitude, and you begin to have a sense of the “family” gathering in court to hear the trial of their patriarch. As we see in season 2 of The Vow, Raniere is on trial for betraying the trust of this family of intimate strangers, perverting their ideals, yet not all are prepared to believe this version of events. You encounter groups of sleepwalkers, at various stages of awakening: some blinking in the new light of self-awareness, still bewildered; others with eyes screwed shut, in firm denial of any wrongdoing on the part of their master, with whom they’ve entrusted the care of their souls.

I remember well the overwhelming six weeks of dispiriting days when I covered this trial with all its unimaginable ghastliness—throughout which the diabolical defendant watched over the macabre theater like an ancient cat, a satisfied sphinx, uncannily composed, with fingers interlocked and lightly resting on his chest. This was his element: humiliation, intimidation, misrepresentation of facts. Yet as grave revelations and his damning crimes continued to be exposed throughout the toxic, cautionary tale of a trial, we would come to see that this self-titled “smartest man in the world” was not nearly as intelligent as he thought. If the Vanguard, as he was called by his followers, were smarter, he would have been aware of the universal truth applicable to all bullies, big and small: controlling others is a spiritual impossibility. Those who try must exist in a state of agitated insecurity. The jailor is never free.

Among the spectators in the courtroom, I recall a young brunette and an older blonde sobbing, their bodies convulsing with sorrow, during the pitiable testimonies. A gentleman with a deep tan and gray hair sat between them, as a steadying force, like a dignified tree with a wizened human face, ringed with concern. Slowly, he extended his arms, like benevolent branches, to comfort and shelter the women in his care from the violent winds of these memories, whipped up by one witness’s testimony.

For some, we learn, the damage had been nearly decades in the making. Some sixteen years before this overdue trial, as early as October 2003, a cover story in Forbes magazine found that “some people see a darker and more manipulative side” to purported self-help guru Raniere, who ran “a cult-like program [NXIVM] aimed at breaking down his subjects psychologically” while “inducting them into a bizarre world of messianic pretensions, idiosyncratic language and ritualistic practices.”

Trust would get you to the idea of enlightenment and freedom, Raniere pronounced, to one of his many bewildered young, vulnerable female victims seeking empowerment and community. This aphorism is a fine example of why half-truths are more dangerous than lies. Yes, it’s a time-honored, spiritual truth that trust leads to freedom. Trust in life, God, love. These are tremendous subjects that have been contemplated for millennia by mystics and lovers of all stripes. Truly loving another, for example, setting aside one’s ego, being vulnerable and surrendering in good faith can serve as a portal for freedom or enlightenment—the way others help us to evolve and to see and be who we cannot become by ourselves. In that sense, surrender and trust are deeply powerful human urges at the heart of world religions, personal relationships, and part of what it is to be a member of the human family.

Similarly, within a philosophical or spiritual context, the idea(l) of master/disciple can be a necessary step along the path of wisdom and liberation. A master is someone who overhears our longing, recognizes our potential, and guides us, selflessly, through their experience, to arrive at our maximum potential and ideal destination. But what this vile master of vice offered through his malevolent filter and devious circular thinking was a bastardization of these timeless, life-giving, and transformative truths. His self-serving and sinister ulterior motives preclude authentic trust, freedom, or enlightenment. Yet, as meaning-seeking beings and trusting creatures, it’s often our tendency to instinctively respond to these powerful, magnetic concepts—alas, sometimes, before we can pause to examine the intentions of the individuals posing these questions. There are words that are so noble, in themselves, we assume that anyone who handles them must be good and wise by association.

There are words that are so noble, in themselves, we assume that anyone who handles them must be good and wise by association.

If one knows nothing else about the NXIVM case but the saga of young Daniela, then that will suffice. Her heartrending story serves as a microcosm of the entire trial and the decadent universe over which Raniere presided. Within the cautionary tale of Daniela’s encounter with NXIVM as a precocious teenager, which The Vow saves for its last episode, one witnesses malevolence in action, criminal abuse of trust and power, corruption of innocence and youth. An entire family submits their will to a false idol, entrusting a so-called Master with their children, and he ruthlessly brings ruin upon them all. Among other atrocities, the wicked leader, Raniere, impregnates three young sisters (having sex with one when she is merely fifteen) and causes lifelong harm. Mercifully, this family drama also features the awakening of (some of) these unfortunate victims—at great personal cost—and affords a revealing glimpse behind the mask of this vicious leader, who flies into a jealous rage when one of his harem dares to fall in love.

Watching this captivating docuseries, it’s natural to question how intelligent, sensitive people allow themselves to be deceived to this extent. The complicated answer is: only when conscience, instinct, and emotions are suspended might one submit to such a warped moral universe. One cannot help but wonder, Could someone with strong family roots, firm guiding principle or values—say, a faith tradition, or a profound knowledge of psychology and philosophy—fall for so much relativizing? Can’t one see cults, in general, and NXIVM in particular as an opportunistic disease, feeding off a cultural malady: superficiality?

One might question further if it’s not varying degrees of lostness that these victims all had in common. Did they not approach, desperately seeking answers, wounded and/or numb, only to be offered a quick fix and a crutch to lean on? If so, just as they felt that they were getting better, finding a foothold and healing, this so-called crutch was taken away and their other leg deliberately handicapped. “You crippled me and used that handicap against me” were the pitiful words replayed in court by one of his underage victims. Watching both seasons of The Vow, one comes to the distressing realization that, despite their differences, all the women were viewed as living puppets, strangely interchangeable for our sick antihero—part toys and part tools to repair his irrevocably damaged psyche.

Only Raniere’s own feelings and thought objects (as he refers to them) are real to him. He cannot profoundly see or feel the hapless others that he sucks into his demented inner drama, reducing them to near-identical broken dolls, soon discarded, compulsively repeating this dark pattern. He is dead inside and frantically, vampirically, in search of fresh blood to survive on and draw life from. Ironically, once he has drained his victims of all their vitality, he feels cheated that they are not their former lively selves and comes to resent them.

In the language of therapist and cult expert Daniel Shaw (from his work Traumatic Narcissists), this sort of behavior is a prime example of the shamelessness of cult leaders feeding off the shamefulness of their followers. One cannot exist without the other, and the independence of the cult leader is another myth. As Shaw elaborates, cult leaders are in need of others to do their dirty work and much else. They are, in fact, utterly dependent on their followers (who, in turn, also become needy, dependent).

There are trials within trials, within this case NXIVM, of increasing subtlety. Past the morality play, modernity itself is on trial—the way we live now—the parameters of choice and responsibility, the tribulations of freedom. More mysteriously, words, ideas, and ideals are also on trial. In the phrasing of German philosopher Heidegger:

Language is the house of being. In its home, human beings dwell. Those who think and those who create with words are the guardians of this home.

What happens, then, when words lose their meaning? When language is unanchored from values and lost at sea?

What happens, then, when words lose their meaning? When language is unanchored from values and lost at sea? As we see in the trial of the shameless, devious Raniere, things have come to mean their opposites: empowerment is slavery, morality is depravity. Weighty words like integrity and ethics, for example, are lightly thrown about, no longer backed by the gold of morals. Yet luminous words, with false intentions, have not lost their power to seduce. This was something they often did, offers one of Raniere’s victims: “take great quotes and writers out of context. It messes with your head.” Inspiring quotes and great ideas, deceitfully repurposed by Raniere and NXIVM, came to mean their antithesis—instead of inspiring others to achieve liberation, condemning them to emotional, intellectual, and bodily slavery. Such is the power of words, even out of context.

This, of course, is not new or strictly relegated to the underworld of cults. Regularly, in the sphere of politics, for example, one witnesses the abuse of language and is made wary of the dangers of eloquence, perfumed words used to conceal what is rotten. Just as words are used to create myths, in the case of NXIVM, so they are also employed to destroy lives. One might put some of these slippery truths into verse, the way I have in a poem:

Words

Certain words must be earned

just as emotions are suffered

before they can be uttered

—clean as a kept promise.

Words as witnesses

testifying their truths

squalid or rarefied

inevitable, irrefutable.

Yet, words must not carry

more than they can

it’s not good for their backs

or their reputations.

For, whether they dance alone

or with an invisible partner,

every word is a cosmos

dissolving the inarticulate.

Several times throughout this bizarre, alarming trial, the term monk comes up, reverently, since despite his immoral promiscuity, Raniere presented himself to many members of his circle as a renunciate. One wonders if behind his maniacal wish to control others is the deep frustration that he cannot control himself. Might it be that, on some level, this sick, cowardly man admires the ascetic ideal yet realizes that he has failed to live up to it and, in turn, projects his self-loathing onto his disciples? Perhaps this is the “truth” that attracts followers to his otherwise false self-improvement model. In Raniere, we see an unwell individual aping a great man, a master, yet constitutionally incapable of embodying the principle he preaches.

Words, meaning, morality: these are building blocks of our existence. As we negotiate how we wish to live, we are often in the process of rebuilding the house of being, throwing out the old and tried in favor of the new and untested. In a cynical age, ignorant of tradition and history or suspicious of organized faith, the fear is that this vacuum is increasingly being occupied by students-posing-as-teachers or, worse, opportunists who style themselves as life coaches and gurus.

Naturally, this patina of spirituality is a disservice to genuine seekers, persuading them to stop short of pursing real ideals in favor of quick fixes and the promises of shortcuts to transcendence. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king, which is why so many, nowadays, seem eager to surrender their longings to con artists or false prophets, bandying about enticing buzzwords.

With organized religion on the wane and spiritual-but-not-religious seekers on the rise, self-help books and self-made gurus loom large, appearing omnipresent and omnipotent. That such books have mushroomed into a lucrative industry at a time of collective purposelessness and laziness is no real surprise. To get a taste for the blind ambition and absence of modesty symptomatic of our confused times, head over to Instagram, for instance, to read some of the outlandish titles that the spiritually immature assign themselves: prophet, sage, visionary, authenticity expert, freedom coach, transformation facilitator, inspirationalist, lightworker, alchemist. The list is as long as it is tragicomic.

It this sort of pastiche of pop psychology and ambiguous yearnings that has made impatient seekers susceptible to New Age philosophy—with its tendency to cherry-pick alluring terms or ideologies out of context to create its cozy patchwork quilt. Those with an axe to grind with religion, who nonetheless seek the comfort of faith or pursue self-improvement more broadly, without personal responsibility and genuine commitment, are natural victims of the easy solace offered by false revelation and distorted theology. This is a sign of our times, a kind of spiritual equivalent to fast food for the starved and undiscerning. It is in such an environment of moral relativism and lack of discernment that malevolent cult leaders like Raniere and his ilk are able to easily stalk their prey. “We’re going to do unethical things, ethically” is Raniere’s morally destabilizing reasoning.

Ft. Lauderdale