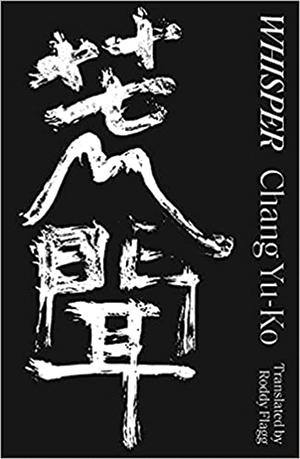

Whisper by Chang Yu-Ko

Handforth, UK. Honford Star. 2021. 294 pages.

Handforth, UK. Honford Star. 2021. 294 pages.

HORROR FILMS FROM East Asia (especially South Korea and Japan) have impacted the cinematic genre for decades and made big business through both international releases and English-language remakes. East Asian horror fiction, by contrast, is almost nonexistent in the anglophone literary market. This mirrors a larger disjuncture between anglophone consumption of East Asian visual media and translation of fiction. But a few gems have appeared in recent years, including Mariko Koike’s The Graveyard Apartment (1993; Eng. 2016), Hye-Young Pyun’s The Hole (2016; Eng. 2017), and Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police (1994; Eng. 2019), the tip of a wave of intense literary horror fiction that continues now with indie publisher Honford Star’s release of Taiwanese writer Chang Yu-Ko’s English-language debut, Whisper—a gruesome yet thoughtful novel of ghosts, vengeful spirits, historical mystery, extreme inequality, and violent colonial pasts.

Whisper opens on a sour note, following a day in the life of husband-and-wife pair Shih-sheng and Hsiang-ying as they drudge through shitty, low-paying jobs that offer no financial security but plenty of stress. Shih-sheng drives a taxi and spends all his money on booze and cigarettes, and his free time on abusing his wife, who works multiple jobs to make ends meet. Stuck in poverty after getting into a debt cycle specific to Taiwan’s medical and legal system, the couple sets the tone for a grim exploration of economic and social inequalities that Chang explores through the stark, nonmoralizing language of realism; until the spooky stuff starts, with Hsiang-ying tortured by a voice and visions that drive her life into disrepair and ruin. Stuck with debt, guilty over abusing his wife, and depressed by his social isolation (caused by his own behavior), Shih-sheng discovers that his wife’s hallucinations were caused by a ghost—one that has killed anyone who hears it for nearly a century.

Chang’s novel is a realist noir whose entirely unlikable stand-in detective pursues a historical mystery that involves his own family and the colonization of Taiwan, first by Chinese, then Japanese imperial powers, resulting in the brutal murder of Indigenous peoples like the Bunun. In addition to Shih-sheng, Chang brings in perspective characters like Hsiang-ying’s social-climbing sister, a disturbing Buddhist priestess, and a social worker, who all collide with Shih-sheng in his frantic search for answers as he too becomes pursued by the ghost. Chang draws on Taiwan’s complex internal history as well as a mix of Chinese, Japanese, and Bunun folklore, and Buddhist and Shinto beliefs, allowing Whisper to reflect on how history undergirds contemporary social and economic inequalities, quite literally haunting the present.

As a horror novel, Whisper elevates the already familiar realist look at the neoliberal violence of daily life in contemporary East Asia with a deft interweaving of history-telling, personal narrative, and scenes of supernatural encounter that move between the tense and the terrifying with alarming ease. Though Chang is unknown in the anglophone world, Shih-sheng’s horrendous encounter with hallucinations of a Japanese woman contorted into an insectlike monstrosity, hanging on ceilings and pursuing him through the woods, will impress even diehard readers of the genre.

Few authors are able to do so much with such a short novel, and to do justice to all the generic and critical elements at play (though I do think Chang’s B-plot about Chen-shan was rather weak). Not much scares me, but Whisper gave me a night of restless sleep, and I’m hopeful that its success will lead to more translations of East Asian horror and a long career for author Chang Yu-Ko.

Sean Guynes

Michigan State University