Writing in the Web of Beings: A Conversation with Henrietta Rose-Innes

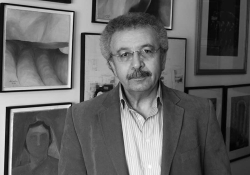

Henrietta Rose-Innes is a South African author of two short-story collections and four novels, including Nineveh and Green Lion. She has won the Caine Prize for African writing (for her story “Poison”) and the François Sommer Literary Prize (for her novel Nineveh, in French translation), and was the runner-up for the BBC short-story competition for “Sanctuary.” She holds a PhD in creative and critical writing from the University of East Anglia and currently lives in Cape Town.

Filippo Menozzi: An important theme in your fiction seems to be the representation of wildlife. For example, your 2015 novel Green Lion revolves around an extinct species of lion. Could you tell me more about your interest in wildlife? Do big cats have a special significance for you?

Henrietta Rose-Innes: My project over the last few books—starting with Nineveh and moving on through Green Lion—has been to explore relationships between the human and the nonhuman world and to blur those boundaries. Nineveh (which dealt with a humane pest-removal expert and a swarm of strange insects) was a rather more bountiful and ebullient take on the subject, looking at how we and the irrepressible nonhuman world around us inevitably overlap and infiltrate each other, defeating the idea of unsullied “nature.” Green Lion investigates the opposite: the melancholy and existential loneliness of a humanity that is systematically eradicating our animal companions on the planet.

Lions are significant to me, yes—especially the Cape black-maned lion. As a small child, I would go to the museum in Cape Town (where my mother worked) to stare at the photo of the last one shot in the Cape; there are no specimens left in the country. Part of my mission in writing this book was to track down that exact specimen, which I eventually did, in the basement of the London Natural History Museum storage facility! That lion in particular is very heavily laden for me with emotional significance, with nostalgia, and memories of my late mother, and with a sense of loss and mortality.

Lions are significant to me, yes—especially the Cape black-maned lion.

Menozzi: I am intrigued by your decision to title the sections of Green Lion with names of animals, from big to very small, including “virus” and even “human” among them. Can you tell me more about this? Does the idea of metamorphosis inspire your work, and should nonhuman animals be read as characters in their own right in your writing?

Rose-Innes: Despite the fact that the book was meant to be sparsely populated, set in a world becoming sterile and losing its animals, I noticed that they kept popping up in the margins, as it were—almost like I couldn’t help myself. So I decided to acknowledge that and to make that half-concealed crowd of living things more explicit by name-checking the chapters in this way: a hint of the teeming life that does still exist. I liked the suggestion of a bestiary.

A number of the animals thus named are not real but symbolic—like Sekhmet the goddess. One thing I wanted to explore was how humans fetishize and mythologize the figures of animals, how they take on such potent symbolic meaning, even as we lose our everyday connection to real wild creatures. The chapter titles, and the many epigraphs, were a way of noting this.

Menozzi: Would you define your writing as a kind of nature writing?

Rose-Innes: Especially in the context of Nineveh and Green Lion, I think I would probably not use that term—the books reject a bright dividing line between “nature” and the human realm. If one was to define nature as a much larger web of beings, human and non—even living and non—then yes, my writing does attempt to grapple with that. It attempts to encompass the nonhuman while acknowledging that the nonhuman must remain to a large degree unknowable.

Menozzi: An inspiring passage of Green Lion describes the postcard reproduction of a painting, Saint Jerome in His Study, which includes the elusive figure of a lion in the margins. Could you tell me more about this painting and your interest in the story of Saint Jerome? Why did you find the lion in the painting noteworthy?

Rose-Innes: The first time I went overseas was to London, and that particular painting in the National Gallery was one of the most important images I retain of that trip. I had it as a postcard on my wall for many years. I was pretty blown away by the sheer riches and the depth of history that were so easily accessed in European cities, that could be experienced simply by walking through the doors of a museum.

I liked the painting in particular because it is so strange, human, even quirky—the story of Jerome and the lion’s friendship itself, and the curious composition of the painting with the tiny lion and little domestic details happening off to the side—it all hints at unexpected, off-kilter stories, aspects of the human experience that could not be accounted for by my then quite conventional understanding of history, art history, Christianity, and the way people behaved in the past. It made it all seem delightfully strange but relatable in unexpected ways.

In the context of the book, I hope the image is poignant too. A lion coming to find you means your death; but the painting domesticates that, makes it feel fond, inevitable; you watch it approach from afar, shyly. But it retains a shudder of the uncanny.

There is of course an added resonance and oddness in seeing images of southern African lions, far from home, being used in Renaissance iconography in this way. So very distant from the savannah and any indigenous context. It is both touching and provocative.

Menozzi: Is your mention of this painting in the novel linked to your travels to the UK and visits to museums and art galleries in Europe? Can you tell me more about the place of Europe in your work?

Rose-Innes: Growing up as white English-speaking South African, immersed in English colonial culture, there was the expectation that the UK, in particular, would be a home away from home. But I never found this to be true. Europe feels very culturally removed—even in the UK, where the language and much else is superficially familiar.

I find this very relaxing! It’s a liberatory space, unattached to the memories and associations of home, and thus for me a good place to write. I have taken advantage of many opportunities to travel and write overseas (praying that I may do so again, once this lockdown is finally done), but my inspiration is drawn from home, from South Africa. I have yet to really feel able or compelled to write about European places, except for a few quite experimental short stories. I’m not sure I will ever be bold enough to tackle a setting that lacks the textures of home.

Menozzi: In a passage of Green Lion, we find a description of the appearance of the lion “unexpected” and as something “coming up in the rearview mirror.” This is a fascinating image. Could you tell me more about it? Why is the lion’s appearance unexpected, and does the image of the “rearview mirror” have any specific implications or connotations?

Rose-Innes: In that book in particular, I believe the lion is death. Green Lion is about loss—but as much about human bereavement and grief as it is about animal extinctions, written as it was when my mother was reaching the end of her life. The rearview mirror is less about hindsight than it is about the unsettling sensation of something always just behind you, small at first, slowly drawing closer, that you avert your eyes from until it is too big to avoid.

Menozzi: Could you tell me more about the origins of your beautiful short story “The Leopard Trap”? The reader joins Daniela, the protagonist, in a search for a feline that does not seem to appear in presence. What inspired the idea of a leopard trap?

Rose-Innes: That particular leopard trap was one I stumbled across while hiking in the Cederberg mountains, north of Cape Town. The kind of material history one can find lying about in the veld in South Africa, fragile, undocumented, often crumbing away, its context lost—as opposed to the often highly tended and curated history of Europe. It was a particularly potent object, with its suggestions of great violence, now stilled; of a creature of great vitality, now absent. An echo of the conflicted rural history of the area and of the barely contained violence that Daniela has left at home.

Menozzi: One aspect I find particularly thought-provoking as part of my reading experience of your fiction could be described as follows: sometimes nonhuman animals seem to suggest they are supposed to be a metaphorical stand-in for another level of meaning, but at the same time, living beings have such a strong presence, which seems to elude any sort of metaphor or allegory. Should nonhuman animals, for example the lions in Green Lion, be read “metaphorically”?

Rose-Innes: I think part of the answer is simply that animals are such seductive subjects to write about: there is an immediacy and sensual thrill in describing, for example, iridescent beetles or tawny lions; it’s possible that I indulge myself. But in the sensual description there is also an attempt to resist metaphor: the animals have their own, essentially unknowable material existences, always beyond human meaning. Their meaning is, in large part, an insistence on their own mysterious, inviolable otherness, and our need to respect and coexist with that. Again, this is in contrast to the other animal figures—the taxidermied bodies, the religious icons, the wildlife specials on the TV—that are our human attempts to instrumentalize animal bodies for our own emotional needs.

Part of it stems from living in a country where there is a lot of suppressed and hidden history, just beneath the surface of landscapes that otherwise present an idyllic face.

Menozzi: In both Green Lion and “The Leopard Trap,” big cats seem to be remarkable because of their ability to escape our field of vision. Is the fact of being elusive and invisible important to you?

Rose-Innes: Part of it stems from living in a country where there is a lot of suppressed and hidden history, just beneath the surface of landscapes that otherwise present an idyllic face—like stone tools of genocided peoples just beneath the surface of the ground, if you dig a little; the Calvinist culture of the apartheid regime, where much was repressed or brutally erased. I grew up in this atmosphere, where the true lion was always just about to step out of the long grass.

More cheerfully, though, the seen/unseen element relates to where I see myself on the continuum of realist and speculative fiction: for me, the magic moment of escape or revelation in writing occurs in the small gap between the real and the unreal, where what you think you know is on the verge of transforming into something other, or something other is on the verge of erupting into the real. For me those moments are what I aspire to achieve in my writing, that’s where the excitement lies . . . the potential of the lion about to emerge is more stirring to me than the lion in full view.

The potential of the lion about to emerge is more stirring to me than the lion in full view.

Menozzi: In Green Lion, you describe, very vividly, a debate around the demolition of a shantytown and fencing Lion’s Head to create a natural reserve. A character in the novel asks: “What do you care more about, the animals or the people?” This is a provocative question as it highlights unsolvable dilemmas around the politics of conservation today. Can you tell me more about this episode in the novel? How is this difficult question meant to be answered?

Rose-Innes: The specific incident is fictional—there are no shacks on Lion’s Head, which is a popular hike and lookout spot. However, there are informal settlements close by, and a great many homeless people in central Cape Town, some living rough on the lower slopes of the mountain. The episode is also, of course, an overt reference to the infamous forced removals of the apartheid years, when whole neighborhoods were bulldozed to make way for white suburbs; to more recent demolitions of informal settlements all over the country; and generally to vast inequality and geographic segregation. The contested spatial history of Cape Town is impossible to ignore and is in constant tension with its natural beauty as advertised to tourists. This tension has always been there—the mountain used to be a hideout for runaway slaves, and during apartheid its desirable lower slopes were reserved for white occupation.

Now, especially with the rise of the tourism industry, there is a tension between the preservation of wilderness areas and the perceived need to keep the poorest of the poor out of them. Wildfires on the mountain, for example, are frequently blamed on homeless encampments’ fires, and there is conflict over hunting and trapping, too. Of course, in Green Lion the conventional conservation measures—fencing people out—turns out to be futile, as the mountain is in fact a sterile place without animals; so the book could be read in part as a critique of conservation philosophies that seek to keep wild areas pristine and exclusionary.

Menozzi: I am fascinated by the representation of space in your writing. The space of the city, architectures, buildings, wilderness . . . Is there a particular kind of space or place that holds a special significance for you, and why?

Rose-Innes: There’s a huge appeal in undefined (to use that terribly overworked word, liminal) spaces: ambiguous zones between city and wilderness. In a country where space has been very severely delineated along racial and socioeconomic lines, the bits in between offer a kind of freedom, safety, and anonymity, even though they may be objectively dangerous. Many of my locations are empty, ruined, abandoned; I like the idea of a writer (or character) as a kind of detective, turning over the traces of human presence—in the absence of living humans. It’s a way of engaging while avoiding overt contact or conflict, which I tend to shy away from (in life and writing!). It’s why I was always very drawn to archaeology, too: the possibility of quietly breaching boundaries, even over centuries, by means of resonant objects. (I have to guard against inserting too many “resonant objects” into my books.)

Menozzi: Another theme I find really interesting in your work is the theme of escape. Would you agree if we were to define your work as a fiction of escape?

Rose-Innes: Personal escape has always been my bedrock motivation for writing—certainly it started out being my motivation for reading as a child. Not so much a desire to escape this world, but to find pockets of otherness within the known world to slip into; or ways to transform the mundane known world into something transcendent. I am not so drawn to outright fantasy. On some childish level, I still have to believe that such a transformation might be possible. I sometimes think my desired literary space, as writer and reader, is not Narnia, or even the Wood between the Worlds—but in fact the Wardrobe. Just as you push your hand through the back of it. . . . Many of my characters seek the same, I think, although I am not sure they often succeed.

I sometimes think my desired literary space, as writer and reader, is not Narnia, or even the Wood between the Worlds—but in fact the Wardrobe.

Menozzi: Your fiction often raises questions about pressing political and social issues, for example the gentrification of neighborhoods or new enclosures. Would you define your fiction as political in any way?

Rose-Innes: I do believe all fiction is political, intentionally or not. Particularly when touching on the immensely loaded issue of claims to the land, one has to recognize how this reverberates through one’s writing. It is in the ground beneath our feet, literally. While I would not consider myself an activist writer, and I don’t write explicitly about contemporary party politics, I consider it part of the responsibility of writing in a contested world to pay attention to history and context, and to engage honestly with it.

July 2021

Henrietta Rose-Innes is a South African author of two short-story collections and four novels, including Nineveh and Green Lion. She has won the Caine Prize for African writing (for her story “Poison”) and the François Sommer Literary Prize (for her novel Nineveh, in French translation), and was the runner-up for the BBC short-story competition for “Sanctuary.” She holds a PhD in creative and critical writing from the University of East Anglia and currently lives in Cape Town.